The latest news shows that the economy is once again taking a turn for the worse. The Eurozone is in recession. China is slowing down sharply. The US is teetering on the brink. Another economic crisis is on the way.

Millions of workers are asking themselves: why does capitalism seem to be in permanent crisis?

It is now 16 years since the beginning of the 2007-2008 crash, and over this entire period one crisis has followed another. Commentators and economists have even coined a new term, “permacrisis”, to try to describe the constant state of uncertainty that the world finds itself in.

This is just another way of describing what Trotsky identified as an organic crisis of capitalism 90 years ago: that is, a state of prolonged crisis, in which capitalism cannot find a new equilibrium.

To understand how we got here, it is worth looking back at the past several years and what prepared the way for the crisis we find ourselves in today. By surveying this period, we can see how all the measures that governments and central banks took to get out of past crises merely prepared the way for new, even deeper difficulties.

The subprime mortgage crisis

The so-called subprime mortgage crisis began in April 2007, when the largest subprime mortgage lender in the US, New Century Financial, filed for bankruptcy, as the bottom fell out of the housing market.

Subprime mortgages and their companions, Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs), were a marvellous invention of the financial speculators. They had lent out $1.3 trillion to ‘subprime’ clients, i.e. people who could not afford to pay. This worked reasonably well, as long as house prices were constantly going up, because the banks could always recover the money they were owed from selling the houses through foreclosures. However, when house prices started falling in early 2007, this very quickly unravelled as the banks could no longer recover the money they were owed.

To make matters worse, in a stroke of genius, they packaged up these mortgages with regular mortgages and sold them on in the form of so-called CDOs. This was meant to spread the risk, thereby reducing the exposure of the specific institutions that were doing the lending. In reality they just spread their losses all across the banking sector in an uncontrolled and opaque way.

Despite the bailout, the Credit Crunch led to a sharp drop in world GDP / Image: public domain

Despite the bailout, the Credit Crunch led to a sharp drop in world GDP / Image: public domain

When 2007 came along, no one really knew who was sitting on what debt. No one knew who was exposed to these subprime mortgages. Suddenly, no one trusted any banks, and no bank trusted any other. The entire banking sector froze up as institutions started collapsing one by one. This freeze became known as the “Credit Crunch”, as banks stopped lending to each other, to businesses and to workers.

In the end, only hundreds of billions of dollars from the state could save the banks. The entire banking sector was guaranteed by the state, and every failing bank, with one or two exceptions, was rescued. The total amount lent by the state reached into the tens of trillions of dollars, although the overwhelming amount of that was paid back as markets stabilised, leaving a bill of a ‘mere’ $500 billion.

At the time, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Barnanke worried in private about a “populist backlash” to this massive bailout policy. And, although it didn’t happen immediately, it did come, both in the shape of the reactionary Tea Party movement, and the anti-capitalist Occupy Wall Street movement.

Despite the bailout, the Credit Crunch led to a sharp drop in world GDP. For example, the US economy fell by a bit more than 4 percent in a year, the German economy dropped by almost 6 percent, and the world economy as a whole by just over 1 percent.

This was the first worldwide recession since the 1930s. It came as a shock, not just to economic commentators who believed that they had brought an end to the cycle of boom and bust, but also to workers, many of whom saw their first serious crisis in their lifetimes.

This was the first serious economic crisis since the 1970s, and was already, at this stage, the worst since the 1930s. It completely transformed the political and economic situation in the world. And to this day, there is no sign of any meaningful recovery. Quite the contrary: things seem to only be getting worse.

The roots of the crisis

The capitalist system is not rationally planned. It is a chaotic system, under which human beings are completely subject to the whims of the market. It’s quite different to feudal societies, for example, in which disasters mainly take the form of diseases, bad weather, and wars.

In the Communist Manifesto Marx and Engels explained capitalist crises as follows:

“It is enough to mention the commercial crises that by their periodical return put the existence of the entire bourgeois society on its trial, each time more threateningly. In these crises, a great part not only of the existing products, but also of the previously created productive forces, are periodically destroyed. In these crises, there breaks out an epidemic that, in all earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity — the epidemic of over-production. Society suddenly finds itself put back into a state of momentary barbarism; it appears as if a famine, a universal war of devastation, had cut off the supply of every means of subsistence; industry and commerce seem to be destroyed; and why? Because there is too much civilisation, too much means of subsistence, too much industry, too much commerce.”

This is a remarkable feature of capitalism: to enter into a crisis because there is too much production, too much trade, too much industry, and so on. The crisis of overproduction constantly recurs under capitalism. And for all the wishful thinking of the bourgeois and their apologists on the left, there really is no escape from it under this system. As Marx and Engels go on to say:

“Modern bourgeois society, with its relations of production, of exchange and of property, a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells.”

Such is the nature of capitalism. It is a society in which remarkable productive forces are created, but no one is able to control them. The only force that would be capable of controlling these forces is the working class through a rational plan. But as long as the means of production remain in capitalist hands, this will never be realised.

Instead, we have an economic system wherein the bourgeoisie attempts to control and regulate the markets. They take measures to solve problems, and these measures in turn only wind up creating much bigger problems. Such has been the trajectory ever since the 1970s.

The crisis of 2007 to 2009 was prepared by the methods used by the capitalists to get out of the crisis of the 1970s. Throughout the 1980s, the 1990s, and the 2000s, they were constantly attacking working conditions, including by undermining wages and through speed-ups – intensifying the pace of work. The welfare state was attacked. All this to raise profits at the expense of the working class.

The crisis of 2007 to 2009 was prepared by the methods used by the capitalists to get out of the crisis of the 1970s / Image: own work

The crisis of 2007 to 2009 was prepared by the methods used by the capitalists to get out of the crisis of the 1970s / Image: own work

Whereas in the post-war period, the share of GDP that went to labour in the form of wages or the social wage (spending on healthcare, pensions, education, etc) had been going up, now it went into decline. So, whilst the productivity of the workers was increasing as a result of new investments in machinery and increasing pressure at work, the money workers actually received was stagnating.

This is the essence of a crisis of overproduction. Workers were unable to buy back the products they produced.

There are, however, ways and means of getting around this problem, at least for a time. The capitalist can invest their profits; but that only has the effect of producing yet more products and raising productivity further, thus intensifying the crisis of overproduction down the line.

The other way to circumvent the issue is by lending money to workers, just artificially extending spending power. What the workers could not get in wages, they could now borrow instead. Central banks over a whole historic period lowered interest rates to make borrowing cheaper. From a high of 19 percent in 1981, the Federal Reserve rate reached a 30-year low of 3 percent in 1993, and a new low of 1 percent in 2003.

Governments played their part by deregulating credit markets. Banks were required to have less money on hand for every loan they granted (i.e. they could be more ‘leveraged’, 1988-2004); restrictions against banks expanding into investment banking and insurance were removed (1990s); regulations against usury were removed (1970s); and, crucially for how things played out in 2007, 1982 regulations removed restrictions on different types of mortgages, thus enabling the subprime mortgage market. Details of this can be found in ‘A Short History of Financial Deregulation in the United States’ by the Centre for Economic and Policy Research.

Household debts as a percentage of disposable income rose in the US from 65 percent in 1983 to 90 percent in 2000, and then to 130 percent by 2007. This was completely unsustainable, particularly with interest rates at 5 percent, to which they had risen by 2007. Household debt service payments reached 13 percent of disposable income. This was all revealed in the financial crash. The raising of interest rates in the period 2004-2006 (from 1 to 5.25 percent) to contain inflation made the new debt that was accumulating unsustainable.

This situation was not confined to the US, but was a global phenomenon. All over the world, self-regulating markets and credit were touted as the way forward. As a consequence, global total debt (owed by households, companies and governments) as a proportion of world GDP rose from 110 percent in 1970 to 195 percent in 2007, almost doubling, and by 2021 it has risen to 247 percent.

All this debt reflected a fundamental contradiction in the capitalist system, which is that the workers cannot buy back all the products they produce. Therefore, they have to be lent the money to be able to keep consuming. But loans, unlike wage payments, have to be paid back, and with interest. So, you inevitably wind up in a situation where the consumption power of the working class will be eaten up, not just by profits going to the boss, but also by paying interest, and paying back all the debt that has already been accumulated.

In essence, the accumulation of debt does not solve the problem of overproduction, but merely postpones the problem – and in the process makes it much bigger, as has been revealed time and time again.

Mountains of state debt

The solution that the bourgeois came up with in 2008-9 was twofold. Firstly, they showered the banks with money from governments and central banks. Secondly, they opened up the purse strings of the government budgets.

The US spent over $800 billion, which was unprecedented at the time. The EU committed €200 billion, Japan $153 billion, and so on. This, however, does not account for increased expenditure on unemployment benefits and other relief for the poorest. The combined impact was massive state deficits, which in many of the larger economies rose to more than 10 percent of GDP.

China was a particularly illustrative example. The Chinese government stimulus amounted to $586 billion, but in a much smaller economy than the US. To keep the wheels turning in the Chinese economy, the central and local governments spent massive amounts of money. This led to an explosion of state debt, even while the economy kept growing at a rapid rate. In the 11 years following 2008, the national debt more than doubled in relation to GDP from 27.2 percent in 2008 to 57.2 percent in 2019.

Overall, across the world, public debt rose from 61.2 percent in 2007 to 76.9 percent in 2010 (IMF Global Debt Monitor, 2022).

The limit of this policy was reached rapidly. In the spring of 2010, Greek government bonds were downgraded to junk status and the government was forced to go cap-in-hand to the Troika (European Commission, the ECB and the IMF) to ask for a bailout. The stringent austerity measures that the Troika demanded devastated the Greek economy and the working class, and gave rise to wave after wave of mass movements.

This signalled the beginning of a new turn, with governments across Europe in particular tightening their purse strings to stave off a widespread default.

But the economy had by no means recovered, and central banks had to attempt to keep the whole debt mountain from collapsing: firstly by lowering interest rates to zero; and then, once the interest rate could be lowered no further, by injecting vast sums of money into the bond markets.

This policy was dubbed “quantitative easing”, and its aim was to bring down borrowing costs for consumers, businesses, and, crucially, governments – although the ruling class wouldn’t admit to the latter publicly. They still liked to maintain the fiction that fiscal and monetary policy were independent, and that the central bank wasn’t underwriting the massive deficits that remained, particularly in the US.

Then, of course, in 2020 came COVID-19. This was a massive shock to the system. All the same measures that had been adopted back in 2009-2012 were now back, but on steroids. No longer was $0.8 trillion sufficient. Now the US stimulus programme stood at $5 trillion!

And the EU, previously reluctant to spend huge amounts of money, proposed a programme of €750 billion. On top of that, the ECB is now bankrolling half of EU governments’ debt, in particular that of Italy and France.

The central banks created even more money to lend to anyone that was willing to take on the debt, and interest rates were rapidly reduced back to zero.

Thus, the capitalist economy was being kept afloat by massive government spending, using credit provided by the central bank. This effectively meant that, like so many times in the past, the central bank was printing money to fund government expenditure; and in the case of the US, it even put thousands of dollars into workers’ bank accounts. And like so many times in the past, this prepared the way for inflation.

The ultra-low interest rates and credit markets flooded with cheap central bank credit made borrowing extremely cheap. But now central banks have been forced to massively hike interest rates to stop inflation spiralling out of control. This puts the question of state debt and deficits in an entirely new light.

Japan is paying 8 percent of its budget towards interest on its 263 percent of GDP debt – and this is without the level of interest rate rises that we’ve seen elsewhere. Every percentage point increase will cost Japan $27 billion by 2026 (and over time, of course, that sum will accumulate).

China’s total public debt is over 120 percent of GDP, and will rise to nearly 150 percent in the next four years. This puts it in the territory of France (118 percent) and Italy (145 percent). And if it wasn’t for China’s massive domestic savings, it would have already led to a crisis.

The total debt in China (including that of households and corporations, as well as government debt) has now reached 295 percent, compared to 257 percent in the US. This constantly rising level of debt reflects the untenable position that the Chinese economy is in.

Economists are now looking at growth rates in China of 2-3 percent, rather than the 6.7 or 8 percent that everyone (including Chinese workers) have been accustomed to. Added to China’s difficulties are the policies of economic warfare directed against it by the US and Europe, as well as problems of an ageing population.

The ageing population is not just a problem in China. This is an increasing problem in the West, as well as Japan. Overwork, low pay, and rising childcare costs are forcing millions of young workers to put off having a family as the capitalist class tries to get out of this crisis by squeezing the working-age population even more.

In a planned economy, this question could quite easily be resolved, but under capitalism in the epoch of decay, it presents the bourgeois with the sense of a looming doomsday.

By the end of this decade, the annual healthcare and pension bill in the advanced capitalist countries would have risen by the equivalent of 3 percent of GDP, according to the Economist. This is no doubt the reason for Macron’s insistence on his pension reforms, for example. Capitalism simply cannot afford these reforms anymore.

The US has only been able to maintain its level of debt and deficit because it is the most powerful imperialist country on the planet / Image: own work

The US has only been able to maintain its level of debt and deficit because it is the most powerful imperialist country on the planet / Image: own work

The Economist produced an article earlier this month entitled: ‘Governments are living in a fiscal fantasyland’, in which they describe how unsustainable current budget deficits are. But no government seems prepared to deal with them. And they draw the conclusion:

“Leaving fiscal fantasyland will be painful, and there will undoubtedly be calls to put off consolidation for another day. But it is far better to make a careful exit now than to wait for the illusion to come crashing down.”

The problem is more acute outside of the advanced capitalist countries, as we have dealt with elsewhere. But precisely because these are the advanced, imperialist countries, what happens there will have an outsized impact on the whole world.

The biggest economy in the world, that of the USA, also has one of the worst budget deficits. The stand-off between the Republicans and Democrats over the debt ceiling is of course a piece of well-rehearsed political drama, but each time it re-emerges, it does so in a more serious manner. Behind the drama lies a genuinely serious problem, for which there is no simple solution.

The government deficit in the US is predicted to average 6.1 percent of GDP over the next decade. But if they keep Trump’s tax cuts (which are set to expire) and keep Biden’s industrial subsidies, it’ll reach 8 percent.

To add to all the other woes, at the moment social security is being bankrolled by trust funds, but they are expected to be insolvent by the early 2030s. As a consequence of massive debt, interest outlays are now already $396 billion, and will only get higher as old government bonds expire:

“After all, as Schwartz [chair of Guggenheim partners] notes, the key reason the US government has been able to ignore the growing debt burden in the past decade is that ultra-low rates meant that ‘we were able to have flat interest rate expense for 17 years while we tripled our deficit. This is now over.’”

Last fiscal year, the average rate paid by the federal government was 2.1 percent, and it’s been around that since 2011. Today, treasury bonds are sold at between 3.43 percent and 5.18 percent, which means that any refinancing will have to be done at a substantially higher rate.

The US has only been able to maintain this level of debt and deficit because it is the most powerful imperialist country on the planet. The position of the dollar as a de facto reserve world currency, and as the main currency for settling international debt and trade, gives the US the power to use the Federal Reserve to effectively tax the world. But even that has its limits, and one such is the increasing prevalence of the use of alternative currencies like the Yuan.

A massive crisis is being prepared, and little is being done to stop it:

“Keith Hall, boss from late in Mr Obama’s time through much of Mr Trump’s, thinks it will take a fiscal crisis to force action. ‘But then we’re looking at really draconian cuts that give us a bad recession, simply because they waited too long,’ he says. ‘Policymakers, Congress and the president, they just don’t take it seriously’.”

Given that much of the economy since the 2008 crisis has been kept afloat by government spending, attempting to reduce deficits threatens to plunge the economy into recession. Of course, should governments attempt to continue to postpone the evil day, the reckoning, when it comes, will be all the worse.

The role of the Central Bank

The central bank already played a key role in the capitalist economy, but it has become even more decisive today. The world markets hang on every word that is uttered by the Federal Reserve, trying to determine whether the rates are going to rise by 0, 0.25, or 0.5 points at a certain point in the future. The economy, and millions of jobs, are in the hands of a few economists, upon whose word hinges the future of humankind.

For a very long time, the perceived wisdom was that the central bank must never print money beyond the limits of the productive potential of the economy. If the central bank attempted to kick-start the economy or fund government deficits with money printing, it would inevitably push the economy into inflation, or even hyperinflation. This was even codified into the Maastricht and Lisbon treaties that govern the European Central Bank, which explicitly banned the ECB from ‘directly’ buying member states’ government bonds.

The world markets hang on every word that is uttered by the Federal Reserve / Image: Federalreserve, Wikimedia Commons

The world markets hang on every word that is uttered by the Federal Reserve / Image: Federalreserve, Wikimedia Commons

From the point of view of the German capitalist class, this was meant as an insurance policy against a repeat of the hyperinflation, and the consequent revolutionary movements, that took place under the Weimar Republic.

At one time all the economists were adamant that banks should be independent, and governments should not meddle in their workings, never mind nationalise them. But this perceived wisdom went out the window. And wherever legal barriers had been erected, they were now circumvented.

Central banks began by lowering interest rates to practically zero. Some even experimented with setting negative interest rates. Then they started supporting the bond markets, buying corporate bonds to reduce the cost of borrowing for banks and companies. These bonds were bought by newly printed, digital, money.

Essentially, quantitative easing meant that the central banks were creating new money, i.e. printing money, and using this new money to buy bonds. This ensured that there was a constant flow of money into bond markets, where corporations and governments go to borrow money (by selling bonds, which is effectively an IOU). This meant that the central banks would ensure that companies could always get access to cheap credit, because the central bank was there to provide it, should others not be forthcoming at a sufficiently low price.

Still, they attempted to avoid buying government bonds. By 2010-2012, this limit had gone out the window, and they began buying government bonds to ensure that governments could keep running deficits, and not have to resort to even harsher austerity measures. Of course, they didn’t buy them ‘directly’ but on the secondary markets, which meant they might have followed the letter of the Lisbon Treaty, but certainly not the spirit of it.

Even this was not enough, as the economy and inflation levels did not respond as they desired, particularly in Europe. And so they started discussing the possibility of so-called ‘helicopter drops’, which meant putting money directly into people’s bank accounts.

As an aside, the IMF recently drew a balance sheet on this entire period since 2010, and the resultant cheap credit. In a working paper, they drew the following conclusion:

“Using ultra-easy monetary policy for extended periods facilitates the survival of zombie firms, adversely affecting non-zombie firms through resource misallocation and reduced market shares, thus hurting economic growth. These findings imply a tradeoff between conducting a countercyclical monetary policy and using an expansionary monetary policy for long periods, which may lead to a combination of low interest rates, low growth, and higher financial vulnerability.”

That is to say, the way that they reinflated the bubble failed to solve any of the contradictions which had been building up, and has instead created an extremely fragile state of the world economy.

Throughout the period of 2013 to 2014, there were attempts to stop bond buying, which failed as the markets panicked. Only by October 2014 was the Federal Reserve able to stop its bond buying. At this point, the balance sheet had grown from $900 billion to $4.5 trillion. About 10 percent of all government debt was owned by the Federal Reserve.

In the Eurozone, the ECB held something like 20 percent of the combined debt of the various governments. The ECB didn’t really abandon their bond-buying programme until 2018, and then restarted it again towards the end of 2019, as the economy took a turn for the worse.

When the pandemic suddenly came along, all these measures were implemented again – but this time much more rapidly, and much more extensively. The fact that little inflation had emerged as a result of the previous rounds of money printing probably made them more confident – and complacent – about launching into even more of the same.

But more importantly: after 11 years of crisis, with massive discontent building, and having seen revolutionary movements erupt as a result, they were desperately trying to avoid a severe downturn, and to show that they could manage the situation. Of course, they did just the opposite.

The ECB launched head-first into another bond-buying programme, which increased its balance sheet from €4.7 trillion to €8.6 trillion in two years. The Federal Reserve, always a bit quicker off the mark, managed to add $3 trillion worth of assets in three months, eventually peaking at $8.9 trillion by March 2022. At this stage, the ECB held assets worth 64 percent of Eurozone GDP, and the Federal Reserve 38 percent of US GDP. The ECB held around 40 percent of Eurozone government debt, and the Federal Reserve 21 percent of US government debt.

In other words, central banks were now underwriting a huge proportion of the economy, and it was having an impact. In the US, the amount of money in the economy (physical and electronic) rose by 28 percent between April 2020 and May 2021, but GDP only rose by 3 percent. This means that the amount of money entering circulation far outstripped the amount of additional value created in the economy.

This time, the expansion of the central banks’ balance sheets was not matched by a reduction in lending in the commercial banks. And many of the factors that previously held back inflation no longer applied. We have dealt with the role of inflation in detail in a previous article, but the consequence of this was precisely to stoke the inflation that we have seen over the past 18 months.

Incidentally, the fiction of an independent central bank was unceremoniously dropped during the pandemic. Instead, governments and central banks were now ‘co-ordinating’ their efforts. In the interest of saving capitalism, legal niceties were put to one side.

In the latest crisis, the central banks have also been marshalled into saving failing banks. This is a sleight of hand, particularly by the Biden administration, to make it seem like the taxpayer will not have to pay for this latest wave of bailouts. But no one really believes it.

The central bank has been pushed into playing an increasingly active role for two reasons. The first is the depth of the crisis, which forces the banks to take measures that were previously unpalatable. The second is the political crisis, which itself is a result of the economic crisis.

In a desperate effort to prop up the system, and government budgets, the ruling class has required the central bank to step in and shore up the governments’ finances, thus enabling them to postpone the final reckoning.

However, they are increasingly forced to choose between a number of equally bad choices. They can’t both save the banking system and the governments’ finances, as well as fight inflation.

If they raise interest rates, they sink government finances, and those of a whole swathe of heavily indebted banks, ‘zombie’ businesses and households. If they rescue the banks, they are keeping the wheels of credit spinning, which they are trying to slow down by raising interest rates. Thus, they are caught between a rock and a hard place.

The inflation that simply won’t go away

In his report on the world economy after the First World War, Trotsky explained the role that money printing played in diving up post-war inflation:

“Simultaneously a superstructure of banknotes has arisen, which is also termed capital. For these banknotes and government bonds – all this is called capital. However, this capital represents, on the one hand, a memory of what has been destroyed and, on the other, a hope of what can be earned – but it does not represent capital that actually exists. It functions as capital, however, as money, and this distorts the shape of the entire society, the entire economy. The poorer the society grows, the richer it appears, regarding itself in the mirror of this fictitious capital.” (p.108-9, ‘World Economy – Report’, Trotsky, 3rd Congress of Comintern, Riddel, To the Masses)

This is very much a similar situation to what we see now. The huge amount of money created by central banks during the pandemic doesn’t represent real value created in production. On top of that, the disruption caused by the war in Ukraine pushed the world market over the edge.

The latest figures show that inflation remains stubbornly high. The US, which was less affected by the energy crisis than Europe, but more by pandemic measures, today has a core inflation rate of around 5 percent. Inflation in the Eurozone is slightly higher at 7 percent, but in Britain it remains at 9 percent.

The fact that interest rates are now almost back to levels last seen in 2007 doesn’t seem to have been sufficient to tame inflation. This is now causing serious worry among the capitalists.

The problem they face is that to bring inflation down they have to slow the pace of the economy. They have to do the opposite of what they did in the previous period. Instead of lowering interest rates, they need to raise them. Rather than making people more able to consume, they need to make them poorer. Thus they are forcing austerity on workers, governments and businesses.

But this is not a simple arithmetic formula, where an x percent interest rate gives y percent inflation, and z percent economic growth. Rather, the whole situation is extremely unpredictable:

“Ajay Rajadhyaksha, global chair of research at Barclays, said the Fed had made clear the process to get inflation under control would not be painless. ‘They want some jobs to be lost. They want some eggs to break. They do not want a widespread banking crisis because then the collapse in demand is non-linear and longer. But a credit contraction? Yes.’”

Central banks can only influence the demand side of the equation, they are incapable of affecting supply / Image: kees torn, wikimedia

Central banks can only influence the demand side of the equation, they are incapable of affecting supply / Image: kees torn, wikimedia

It is clear that raising interest rates will cause the economy to slow down and put a downward pressure on inflation – but how much and how quickly is a complete unknown. The real worry is not a couple of quarters of recession; in fact, that already forms part of the predictions of the Federal Reserve. Rather the fear is that they will provoke a 2009-style downturn, or worse.

“‘With any further rate increase, the risk that something breaks increases,’ said Carsten Brzeski, an economist at ING Bank.”

The central bank is forced to constantly look in the rearview mirror to try to work out where it is going. The effect of interest rate rises is slow, and takes many months and years to fully work its way through the system. Mortgages typically have fixed interest rates for a certain amount of time, as have government and corporate bonds, and people will pay off their mortgages with a finite amount of savings, etc.

We know these rates will have a devastating impact on government budgets, households, and corporations. What we don’t know is how quickly this will happen, or how devastating it will be. How many families will lose their homes? How many workers will lose their jobs? How much will governments cut spending? No one knows this in advance. But we will find out in practice in the coming months and years.

The situation is made even worse by the fact that central banks only have a very blunt instrument to fight inflation. The Financial Times in an article earlier this year estimated that 40 percent of inflation was caused by lack of supply and 40 percent by “excess” demand. That is, the extra money floating around in the economy is only part of the story, as we explained. If that was the only problem, central banks would have had a lot more success in combating inflation by now – but it is not.

Central banks can only influence the demand side of the equation. That is, they are capable of making workers, companies, and governments poorer, thereby reducing the inflationary pressure. But they are incapable of affecting supply – i.e. productivity, supply chains etc.

So, when the cost of production keeps increasing – because of protectionism, supply chain problems, wars, or climate change – all the central bank can do is to try to reduce the amount of money that workers have to consume, thus cutting poor people out of certain markets, like meat consumption or housing, forcing them to live off cheaper alternatives, or go without altogether. All they can do is impose austerity on the working class, governments, and corporations.

Because capital is in the hands of the capitalists, the central bank cannot raise the level of investment, which would reduce bottlenecks, raise productivity, and thereby put a downward pressure on inflation. On the contrary, supply-side costs are continuing to rise through protectionism, wars, climate change, and increased military expenditure.

This means that central banks will have to push even harder on the brakes. And they could end up getting the worst of both worlds: inflation and recession at the same time. The crisis of the banking sector in the previous month is the first warning of precisely the kind of pressure that is now being put on the economy.

The banking crisis

That the recent banking crisis started in Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) is not an accident. The IT sector was suffering the consequences of falling advertising revenue as a result of interest rate hikes, and most of SVBs customers were in the IT sector. Much of the boost that was given to the IT sector during the pandemic proved temporary, and as the economy shifted into more normal patterns, revenues fell. This had a direct impact on the deposits of the bank, which mainly catered to this sector.

To compound its problems, the bank had (as often is the case with bank failures) borrowed short and lent long. That is, their depositors could withdraw their money at any time, but the bank had lent this money to the US treasury on 10-20 year terms through treasury bonds.

This wouldn’t have been a problem two years ago, when the bank could simply have sold these bonds to cover the deposits. But the sharp rise in interest rates had caught the bank off-guard. Were they to sell these bonds, they would have to mark down the value of them to reflect the fact that their bonds had a much lower interest rate than what was available if you purchased newly-issued government bonds. To avoid this problem, they attempted to issue new stock, which was the final straw that caused a panic among depositors.

A similar process took place in the bank Signature, which had lots of customers in commercial property. First Republic, which is the latest bank to collapse, had a similar problem in that they had lent to customers on very long terms, at very low interest rates. But now, of course, the mortgage market looks completely different to before. Therefore, if they were to attempt to sell these mortgages on, they would have to take a big loss. When depositors started withdrawing their money, the bank could no longer maintain the fiction that these mortgages were worth the same as they had been before the interest rate rises.

Four academics in a recent paper estimated that, if US banks readjusted their books to the present value of their assets, they would have to write off $2.2 trillion worth of assets. A massive amount of fictitious capital equivalent to 1/10 of the US economy. Of course, as long as their depositors keep their money in the banks, this fiction can continue.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), set up after the bank-runs of the 1930s, is supposed to mitigate against risks like this by guaranteeing all deposits up to $250,000. However, for the rich and businesses, this is not nearly enough, as they have much bigger amounts in the banks. The bank runs show just how nervous the capitalist class is about the stability of its own system.

The way they have dealt with the crisis has important implications:

- It has massively monopolised the banking sector. Many deposits have fled from small and medium-sized banks to the biggest banks. On top of that, the government and the FDIC have begged the big banks to take over the customers of the smaller banks and offered them massive subsidies to do so. The merger of Credit Suisse and UBS combined the two main banks in Switzerland, which means there is now only one left.

- Of course, they are enriching themselves further. Many banks are massively profiting from the new situation. HSBC, for example, earned a record $12.9 billion profits and can expect another $1.5 billion in profits from their one pound take-over of SVB UK.

- The FDIC rescues have wiped out shareholders. Therefore, shareholders, who previously thought their investments in banks might be relatively safe, are now running away from mid-sized bank investments. Of course, this also increases monopolisation.

- In order to replenish the FDIC, they will raise the premium for the big banks, which makes the crisis of the small banks potentially also a crisis for the big banks.

- The Federal Reserve has once again become the lender of last resort. It is now guaranteeing all deposits in all banks, and they are offering to take assets at their book value rather than their market value. This will mean that, as the banking crisis continues, the losses will accumulate in the Federal Reserve.

In other words, in trying to mitigate this banking crisis, the bourgeoisie are preparing new problems for themselves.

The end of globalisation

One of the most decisive questions that the bourgeois have to deal with is that of protectionism and free trade. Lenin explained that the narrow, limited borders of the national market hemmed in the productive forces. Therefore, each capitalist nation, once the productive forces had developed to a certain degree, was forced to attempt to overcome this barrier. When the productive forces developed during the 20th century, world trade developed far quicker.

This was particularly the case for the second half of the 20th century, when the world market managed to penetrate every corner of the planet. The consequences were tremendous, as we pointed out in the mid-1990s:

“The intensification of the international division of labour, the lowering of tariff barriers, and the growth of trade, particularly between the advanced capitalist countries acted as an enormous stimulus for the economies of the national states. This was in complete contrast to the dismemberment of the world economy in the period between the Wars, when protectionism and competitive devaluations helped to turn the slump into a world depression.” (A New Stage in the World Revolution)

One of the most decisive questions that the bourgeois have to deal with is that of protectionism and free trade / Image: own work

One of the most decisive questions that the bourgeois have to deal with is that of protectionism and free trade / Image: own work

Globalisation kept inflation down for an entire historical period. Relatively inexpensive computers, telephones, televisions, and other things made workers feel like they were better off. At the same time, the low interest rates also made it possible to buy houses and the like, even though they became more and more expensive compared to wages. In this way, it was possible to keep wages down, profits up, and at the same time have some political stability.

But now this situation is turning into its opposite. The CEO of BlackRock stated: “The Russian invasion of Ukraine has put an end to the globalisation we have experienced over the last three decades.” What he was referring to was the opening up of Eastern Europe, and in particular Russia and China, to the world market. Now, this new world market is fracturing into different blocs and spheres of influence, which is the real content behind the terms ‘friendshoring’ and ‘reshoring’. These are euphemisms for the word they don’t want to use: protectionism.

The concrete result of this is not hard to see. The East China Sea has been built up as the centre of world manufacturing for decades. China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan all play an essential part in these supply chains. It is extremely difficult to disentangle China, and increasingly also Taiwan, from this web of suppliers. No single country is able to replace China, so companies are looking at building productive capacity in a number of different countries. As the Wall Street Journal put it: “The diversification, which some experts call multishoring, also reflects a stark new reality: The world is a far more complicated place to do business than it was a decade ago.”

Whereas 20-30 years ago, US imperialism was the guarantor of free trade and open markets, it has been at the forefront of a protectionist trend: “America First”, as Trump put it. However, Trump is just putting in a more crude way a set of policies shared across both parties in the US.

In a recent speech, US trade representative Katherine Tai explained how the policy of her administration (i.e. that of Biden) was a break with the past: “For too long, our trade policies have been focused on liberalisation, efficiencies and lowering costs.” In other words, for too long US governments were pushing for free trade. Now they’re pulling in another direction.

Biden kept Trump’s sanctions against China, but has also introduced additional measures, particularly targeting the semiconductor industry. Biden also has continued to block the appointment of new judges to the WTO higher tribunal, demanding “reforms” of the WTO, i.e. more scope for the US to introduce protectionist measures. In the meantime, the US government appeals every decision that goes against it to the very same tribunal. This has completely paralysed the WTO.

Biden furthermore introduced the Inflation Reduction Act, which provides subsidies for US companies. These target partly China, but also Europe and Japan. This begs the question: what does the ‘friend’ in ‘friendshoring’ really mean? In the middle of a period where Europe’s industries are in crisis due to the sanctions against Russia, Biden is rubbing salt in the wound by subsidising American-made goods at the expense of his European ‘allies’. European leaders were not happy, and Macron, for instance, called for a “Buy European” aid package in response.

The IMF warned in its latest report that so-called ‘friendshoring’, or the division of the world economy into two spheres, would reduce the annual growth of the world economy by 2 percentage points. At the same time they are predicting world growth to be merely 2.8 percent this year.

Essentially, reversing globalisation will be very costly, and the world economy will pay the price through higher prices and lower growth. The successes of the past 50-70 years, during which the capitalists partially overcame the limits of the nation state and narrow national market, are now being thrown into reverse.

And then there’s climate change…

To all the economic, political, and social problems that capitalism is facing, we must add the question of the environment and the climate. Here we have a crisis that is only getting worse the longer they wait to deal with it – and they have been postponing doing so for decades.

The transition to renewable energy is now underway to some extent. But from the point of view of climate change, the transition is far too slow, while from the point of view of the capitalist economy, it is far too fast. The investments that are being made are causing all kinds of shortages of raw materials and pushing up costs, provoking more inflation.

The McKinsey Global Institute suggested that the economy would need an additional $3.5 trillion in investment in related industries every year to make a net-zero target by 2050. This represents an increase of 61 percent. An additional $1 trillion would have to be reallocated from what they call ‘high-emission’ investment to ‘low-emission’ investment.

They furthermore declare that this $3.5 trillion would only be half of global corporate profits. If we take these figures at face value, this would mean that, if corporations gave up only half of their profits, we could manage the goal of net-zero. Imagine, then, what we could do if all the profits were invested.

The private ownership of the means of production is revealed as the decisive barrier to tackling climate change / Image: Huangdan2060

The private ownership of the means of production is revealed as the decisive barrier to tackling climate change / Image: Huangdan2060

But the whole thing is a pipe dream. Companies will not give up half their profits, and most certainly not in a timely manner. It is even doubtful to imagine they will reallocate $1 trillion of high-emission to low-emission investments.

The figures provided by the McKinsey Global Institute do not so much show the opportunities that exist under capitalism, as the fact that the money for the green transition is there, but that it’s just being appropriated by the big corporations for private profit. The private ownership of the means of production is revealed as the decisive barrier to tackling climate change.

At the same time, the cost of dealing with natural disasters and switching to new crops, as well as other adaptations, is increasing the cost of everything. This is already having an impact. The weather disasters in New Zealand for example influenced its central bank’s recent decision to raise rates, and this is a sign of things to come:

“‘The impacts of weather disasters will only make the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s job of curbing inflation more challenging,’ said Nick Tuffley, chief economist at ASB.”

The water companies in Britain are poisoning the rivers and the sea, and are now warning that Britain will face acute water shortage within a decade due to shifting weather patterns. Northern Italy last month experienced massive flooding after a period of a very long drought. This will of course cause damage and disruption to the economy.

The climate is a clear example of how capitalism has reached a dead end. It can’t deal with the most important issues facing humanity. The resources are there, the science is there, but capitalism stands as a barrier. It’s a case of too little, too late.

Permacrisis: the new normal

Economists always come up with new buzzwords. The buzzword of the year 2022 was ‘permacrisis’, as recognised by the Collins dictionary. Alex Beecroft, the managing director of Collins Learning commented on the new word:

“It is understandable that people may feel, after living through upheaval caused by Brexit, the pandemic, severe weather, the war in Ukraine, political instability, the energy squeeze and the cost-of-living crisis, that we are living in an ongoing state of uncertainty and worry.”

The new word expressed the profound sense of helplessness and pessimism that the capitalist class feel towards the new political and economic situation.

The word found itself in an article by the European Policy Centre, back in 2021, where the authors, quite empirically, have drawn the same conclusions about the present period that Marxists drew some time ago. They write: “The world we live in will continue to be characterised by high levels of uncertainty, fragility and unpredictability.” They argue that the European Union has to change to adapt to the severe challenge of this “age of permacrisis“.

Christine Lagarde echoed this sentiment in a speech to business leaders in April last year:

“Some say that we live in an age of ‘permacrisis’, where we move seamlessly from one emergency to the next. In just over a decade, we have faced the largest financial crisis since the 1930s, the worst pandemic since 1919, and now the most serious geopolitical crisis in Europe since the end of the Cold War.”

Neil Turnbull, an academic at Nottingham Trent University, summed up what the word implied in an article last November:

“Permacrisis signals not only a loss of faith in progress, but also a new realism in relation to what people can cope with and achieve. Our crises have become so complex and deep-seated that they can transcend our capacity to understand them. Any decision to tackle them risks only making things worse. We are thus faced with a troubling conclusion. Our crises are no longer a problem. They are a stubborn fact.”

For the capitalists, every new crisis appears as something unique; something novel and unrelated to all the other crises. Naturally, none of them are prepared to draw the obvious conclusion: that the problem isn’t just this or that crisis, but a crisis of the system as a whole. The bourgeoisie, and the commentators, academics, and journalists that serve them, have no interest in exploring or exposing the interconnectedness of the crisis.

But in reality this “permacrisis”, or “polycrisis” as it has also been called, is merely another way of expressing, in a mystified way, the crisis of capitalism. Without explaining why, they quite correctly draw the conclusion that we are living in a period of permanent crisis and upheaval.

An organic crisis of capitalism

This is not the first time that humanity has to live through such a crisis. The whole period 1914-1945 was a period of deep crisis, of revolution and counter-revolution. As this crisis unfolded in the first years after the First World War, it provoked some discussion in the Communist International, because it was a new development.

Prior to this, Marx and Engels had quite correctly described the constantly recurring crises of capitalism, as in the following passage from Anti-Dühring:

“The stagnation lasts for years; both productive forces and products are squandered and destroyed on a large scale, until the accumulated masses of commodities are at last disposed of at a more or less considerable depreciation, until production and exchange gradually begin to move again. By degrees the pace quickens; it becomes a trot; the industrial trot passes into a gallop, and the gallop in turn passes into the headlong onrush of a complete industrial commercial, credit and speculative steeplechase, only to land again in the end, after the most breakneck jumps – in a ditch of a crash. And so on again and again.” (Engels, Anti-Dühring)

Drawing all the wrong conclusions from these writings, when the crisis struck in the 1920s and 1930s, the Social Democrats took comfort in the fact that, even if there was a crisis, there would be a recovery, and so there was little need to overthrow capitalism. The German Social Democrat Minister of Finance, Rudolf Hilferding, took this to the extreme length of arguing for austerity, on the grounds that the crisis had to be allowed to run its course.

Trotsky took issue with this dry, mechanical interpretation of what Marx had written, pointing out that this was linked to reformist ideas. He wrote:

“This concept of automatic development is the most important characteristic of reformism. Of course capitalist equilibrium would be re-established, if only the social expressions of class struggle did not intervene in this cruel game.” (p.124, ‘World Economy – Report’, Trotsky, 3rd Congress of Comintern, Riddel, To the Masses)

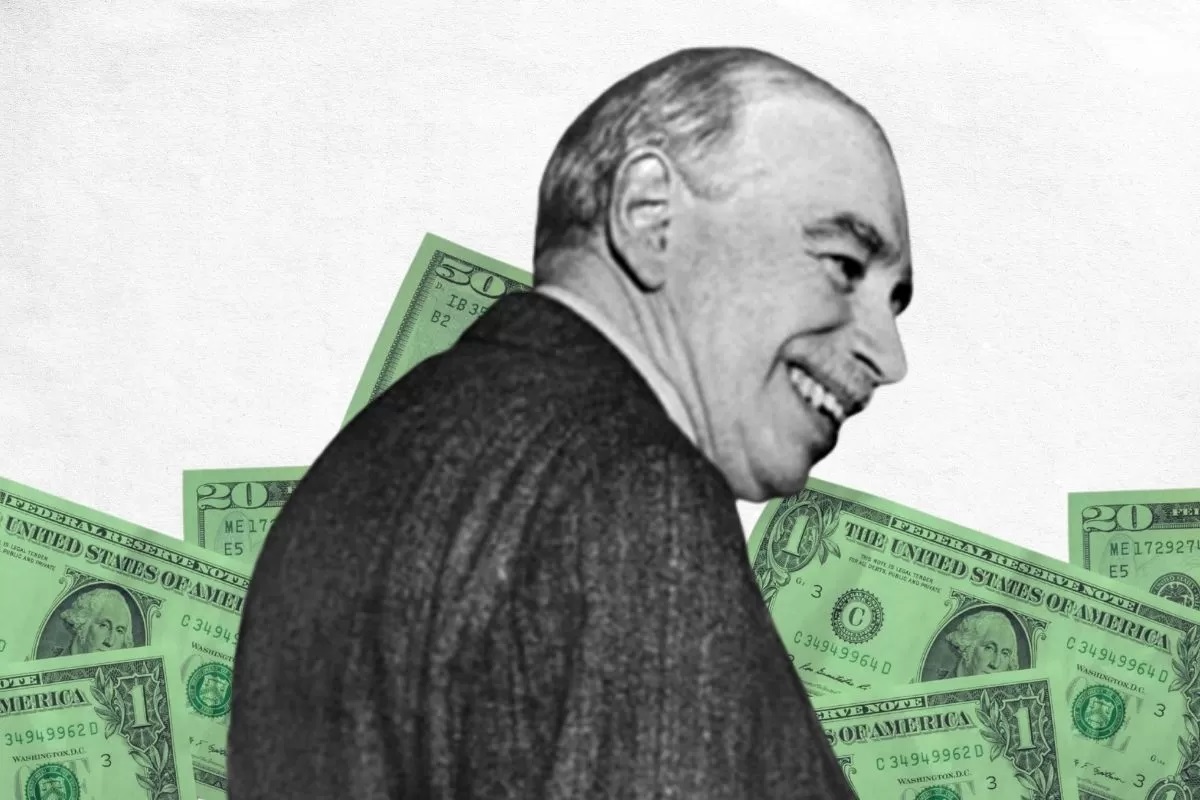

Essentially, crises could be resolved much more easily under capitalism, if workers just quietly accepted their fate of austerity, wage cuts, starvation, and misery. John Meynard Keynes, who famously advocated for precisely the kind of policies that Hilferding opposed, understood this. He famously argued against the neoclassical economists that “in the long run we’re all dead” and that wages don’t tend to fall automatically, just because it suits the equations of the economists. Basically, human beings aren’t just numbers on a sheet of paper, and workers are disinclined to accept starvation in order to preserve the capitalist system.

Normal, brief, cyclical crises could very well pass by without a fundamental break; with a brief tightening of the belt on behalf of the workers, and then a return to normal. But Trotsky is referring to something that went beyond that. The crisis of the 1920s and 1930s, just like the present crisis, was of a different character.

Trotsky noted at the 3rd Congress of the Comintern:

“Rise, decline, and stagnation – along this curve there are fluctuations, that is, improvement in the economy or crisis, but they do not tell us whether capitalism is developing or declining. These fluctuations are like the heartbeat of a living person. The heartbeat shows merely that he is alive.” (p.121, ‘World Economy – Report', Trotsky, 3rd Congress of Comintern, Riddel, To the Masses)

He insisted that although there were ups and downs, the general character of the period was one of stagnation:

“Europe's economy can only shrink and shrivel, in order to achieve a degree of inner coordination. The curve of development of the productive forces will decline from its present fictitious heights. In such conditions, an upswing can only be brief and primarily speculative in character. Crises will be lengthy and profound.” (p. 905, ‘World Situation and Tasks’, 3rd Congress of Comintern in Riddle, John, To the Masses)

John Meynard Keynes famously advocated for precisely the kind of policies that Hilferding opposed / Image: Socialist Appeal

John Meynard Keynes famously advocated for precisely the kind of policies that Hilferding opposed / Image: Socialist Appeal

Trotsky explains that, even if the general epoch has periods of recession and recovery, ups and downs, the general character of the epoch is one of stagnation and crisis. Trotsky returned to this theme in the 1930s, when he described the situation as one of “organic crisis”:

“The economic revival of the past year has, it is true, somewhat damped theoretical searches and social criticism. Hopes arose that the process of economic growth interrupted by the crisis would again be re-established. But sooner than one could have expected the hour of a new crisis struck. It started from a lower level than the crisis of 1929 and is developing at a more rapid tempo. This demonstrates that it is not an accidental recession nor even a conjunctural depression but an organic crisis of the whole capitalist system.” (My emphasis, ‘Trotsky Urges Backing for Pioneer Publishers’, 1937.)

This perfectly describes the position that we find ourselves in today, as dealt with in detail by Rob Sewell in an article from 2015. Just as the bourgeois think that they have turned a corner, so another crisis rears its ugly head. This is what we have seen ever since 2008. The capitalist system is unable to find a new equilibrium.

“A new stage must begin, in order to eliminate the contradiction between this superstructure of fictitious wealth and the poverty that underlies it. The economic body will continue in the future to be wracked by spasms of this type. Altogether, as I have said, this offers us a picture of profound economic depression.” (p.127, 'World Economy – Report', Trotsky, 3rd Congress of Comintern, Riddel, To the Masses)

The depth of the crisis reflects how capitalism has outlived its historical role. The productive forces are in open revolt against the constraints the capitalist system puts upon them: the nation state and private ownership. Capitalism can no longer develop the productive forces, it can no longer take humanity forward. Taken as a whole, all that awaits us in this system is more crisis, and more misery.

The looming recession

The latest economic data show that a new recession is on the way:

- May saw the seventh consecutive contraction in manufacturing, according to the Institute for Supply Management.

- Demand for business loans in the eurozone has fallen at the fastest rate since 2008.

- 45 percent of economists believe in a global recession this year.

- Loans in “serious delinquency” in the US are ticking up in a way they haven’t since 2007.

- According to the latest figures, the Eurozone entered a recession in October last year.

- At the same time, Eurozone inflation rose for the first time in six months to 7 percent.

With the ECB raising interest rates this week to 3.5 percent, it means we now will have a deepening recession with inflation, i.e. the worst of both worlds. But things aren’t much better in the US:

“‘There is a little bit of a tendency to kind of breathe a sigh of relief on mornings like this,’ David Hunt, chief executive of $1.2tn asset manager PGIM, told Milken attendees digesting the First Republic rescue. ‘Actually, we’re just starting the implications for the US economy.’ ‘First of all, we’re going to see a real ratcheting-up of regulation in the banking system, particularly on many… regional lenders,’ said Hunt… ‘What that will do is… further hinder the supply of credit that’s going into the economy. And I think that we are going to see now a real slowing that begins to happen to aggregate demand.’”

Credit is about to get much tighter, meaning less money for workers to consume, job cuts in corporations and austerity in government finances:

“‘That’s a primed-for-disappointment situation,’ said Karen Karniol-Tambour, co-chief investment officer of hedge fund giant Bridgewater Associates… ‘It’s time for the markets to fully digest how constrained central banks are going to be relative to the last 30, 40 years, when every time there was a tiny murmur of a problem, you could just lower rates [and] print money.’”

All the contradictions that have been piling up over the past few decades, all the attempts to reinflate the bubble, all the attempts to postpone the evil day – all those are now coming back to haunt the bourgeois class. One after another, the bourgeoisie have used up the tools they have to postpone the crisis, and they can no longer delay the inevitable.

Will there be a permanent crisis?

When faced with the crisis of the 1920s and 1930s, the question was posed whether this was the ‘final’ crisis of capitalism. Trotsky replied to this that there was no such thing, that capitalism has no predetermined number of crises. Only the working class can put an end to the system:

“Capitalism in its death throes, as we know, also has its cycles, but these cycles are declining and diseased. Only the proletarian revolution can put an end to the crisis of the capitalist system.” (Once Again, Whither France?, Trotsky, 1935)

The profound sense of pessimism, even despair, that affects the world today, in everything from the economists to culture, is a sign that the capitalist system can find no way out. We find ourselves suspended in midair, between what can be and what has been, between the tremendous possibilities that could be opened up with the productive forces that capitalism has created and the reality of a system that is completely incapable of taking advantage of them.

Yet this cannot last forever. At a certain point it has to be resolved one way or another. In the 1920s and 1930s it took two world wars, and 20 years of economic turmoil in between, for capitalism to find a way out. The human cost was tremendous, with more than 100 million dead and a continent devastated. What price would capitalism extract this time?

Rosa Luxemburg in the Junius Pamphlet, written in prison during the First World War, argued that we faced a choice:

“[E]ither the triumph of imperialism and the collapse of all civilization as in ancient Rome, depopulation, desolation, degeneration – a great cemetery. Or the victory of socialism, that means the conscious active struggle of the international proletariat against imperialism and its method of war.”

Today, with the environmental destruction, and the depth of the economic and political crisis, it is quite possible that civilization will not survive another attempt of capitalism to restore its equilibrium.

It is for this present generation to determine what path we will take. It is the task of the communists to prepare the way for humanity to take the next leap forward.