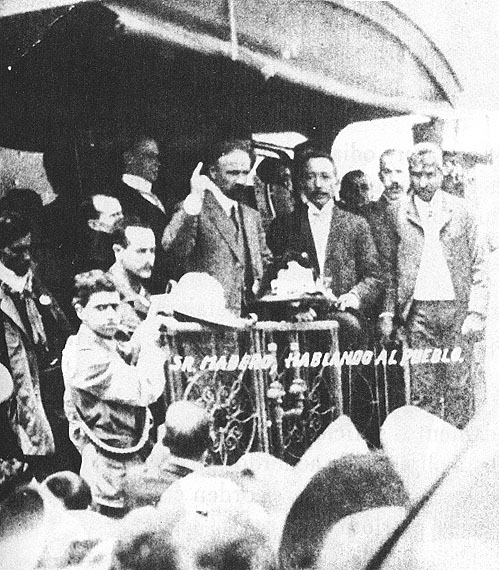

This year marks the hundredth anniversary of one of the great events in modern history. On November 20th of 1910 Francisco I. Madero denounced the electoral fraud perpetrated by President Díaz and called for a national insurrection. This marked the beginning of the Mexican Revolution. Today, the conditions have matured for another revolution, this time with a mighty proletariat at its head.

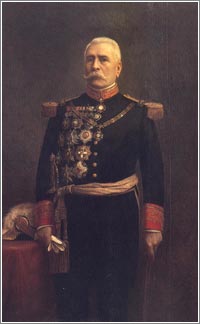

For most of its history Mexico was dominated by a small elite that held in its hands the lion’s share of its wealth, while the majority of the population lived in conditions of crushing poverty. Under the leadership of General Porfirio Díaz, the rift between rich and poor became transformed into an unbridgeable abyss.

Opposition to Díaz emerged under the leadership of the liberal bourgeoisie, people like Madero. But the real motor force of the revolution came from below. The infant Mexican working class was beginning to find its feet. Important labour struggles, starting with the Cananea miners' strike, were shaking Mexico. Feeling the ground quake beneath his feet, Díaz was forced to hold an election in 1910, but in order to make sure he won it he threw his main opponent, Madero, in prison.

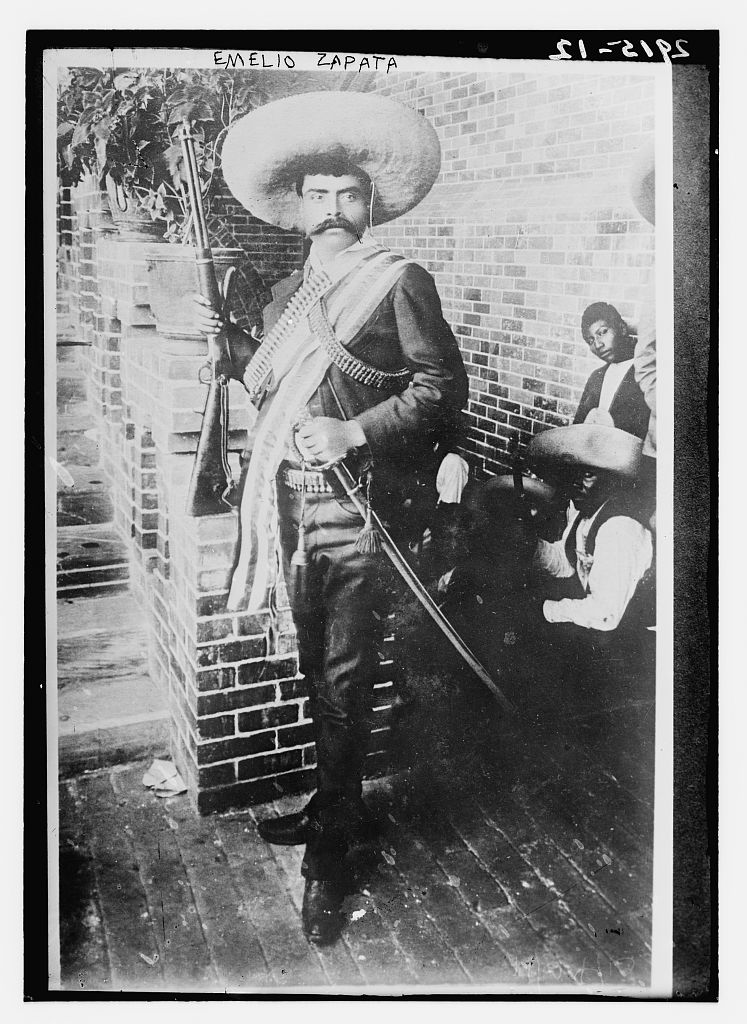

After fleeing from prison, Madero continued his battle against Díaz. He declared that the elections had been fraudulent and called for a national uprising against the Porfiriato. But the struggle for democracy, in order to succeed, had to be linked to the most urgent demands of the majority of the population – the peasantry. The peasants’ struggle for land was the real motor force for the bourgeois-democratic revolution. The peasant armies of Pancho Villa in the north, and the peasant leader Emiliano Zapata in the south harassed the Mexican army in a classical guerrilla war.

The permanent revolution

It is not possible to understand the Mexican Revolution without reference to Trotsky's theory of the permanent revolution. The essence of this is that the colonial bourgeoisie and the bourgeoisie of the backward countries are incapable of carrying out the tasks of the bourgeois democratic revolution. This is because of their links with the landlords and the imperialists. The banks have mortgages on the land, industrialists have landed estates in the country, the landlords invest in industry and the whole is entangled together and linked with imperialism in a web of vested interests opposed to big change.

Porfirio Díaz That is why, although Russia in 1917 was a backward country like Mexico, the task of carrying out the bourgeois-democratic revolution fell on the shoulders of the proletariat. But the proletariat, having conquered power at the head of the peasantry and the majority of the nation, could not stop at the accomplishment of the bourgeois-democratic tasks of expropriating the landowners, unifying the nation, and expelling the imperialists. It passed on immediately to the socialist tasks: expropriation of the bourgeoisie and the setting up of a workers' state. This was the only way in which the enormous potential of the Mexican Revolution could have led to a complete social transformation.

Porfirio Díaz That is why, although Russia in 1917 was a backward country like Mexico, the task of carrying out the bourgeois-democratic revolution fell on the shoulders of the proletariat. But the proletariat, having conquered power at the head of the peasantry and the majority of the nation, could not stop at the accomplishment of the bourgeois-democratic tasks of expropriating the landowners, unifying the nation, and expelling the imperialists. It passed on immediately to the socialist tasks: expropriation of the bourgeoisie and the setting up of a workers' state. This was the only way in which the enormous potential of the Mexican Revolution could have led to a complete social transformation.

The weakness of the Mexican revolution was the weakness of a peasant revolution. The peasantry was strong enough to overthrow the existing order, but not to put its decisive stamp upon Mexico’s historical destiny. This is no exception to the rule. Ever since the Peasants’ Revolt in Fourteenth Century England and the Peasant War in Germany in the Sixteenth Century, all history shows that the peasantry is not capable of playing an independent role. Ultimately, the outcome of the struggle is decided in the towns and cities, not in scattered rural areas.

The peasantry, by its very nature a class of individuals not bound together by production, is therefore the perfect instrument for bourgeois or proletarian Bonapartism. It is a class that can be manipulated and deceived. For most of history, the fate of the peasantry has been to play second fiddle to the bourgeoisie, which has used the peasantry as a battering ram to overthrow its feudal enemies, and to install itself in power.

Such was the rottenness of the existing order that the insurgents succeeded in wresting control from the government forces in their respective regions. The peasant insurgency spread like wildfire. The peasant armies of Zapata showed tremendous courage and determination fighting against the old oppressors. But in the end the revolution was taken over by the bourgeoisie and its political representatives.

Díaz was forced to recognise defeat and resigned in May, 1911. He then fled to France after the signing of the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez, and Madero, the Mexican Kerensky, was elected president. But the new bourgeois government did not satisfy the expectations of an aroused peasantry. Under the leadership of the real hero of the Mexican revolution, Emiliano Zapata, the peasant war continued. Madero's appeals to the peasants to wait patiently for an orderly land reform fell on deaf ears. The peasants had already heard too many empty promises from men in power who pretended to have their interests at heart.

A revolutionary war

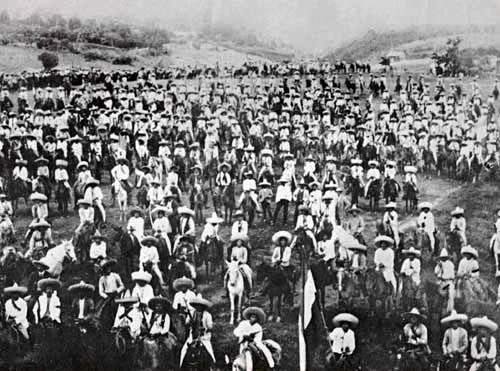

In November 1911 Madero had assumed power, but he was arrested and executed by reactionary army officers. This provoked a new peasant uprising, which wiped out the remnants of the Porfirista army. Zapata moved to take power in the state of Morelos, where he carried out a revolutionary agrarian programme. He drove out the landowners and distributed their lands among the peasants. Zapata used guerrilla tactics, but Villa's Division del Norte was more like an army. The armies of both Zapata and Villa were very well organized and defeated superior forces because they were revolutionary armies, waging a revolutionary war against the exploiters. This is a point that is often obscured in the official histories of the Mexican revolution.

Emiliano Zapata The most decisive role in the revolution was played by the oppressed and the poor (peasants as well as rural labourers). These were the poorest of the poor, people with very limited formal education. Brought to their feet by the revolution, the men and women of no property fought like tigers. Poorly armed and without formal military skills, they inflicted one defeat after another on the government forces in spite of the latter’s machine guns, artillery and professional officers.

Emiliano Zapata The most decisive role in the revolution was played by the oppressed and the poor (peasants as well as rural labourers). These were the poorest of the poor, people with very limited formal education. Brought to their feet by the revolution, the men and women of no property fought like tigers. Poorly armed and without formal military skills, they inflicted one defeat after another on the government forces in spite of the latter’s machine guns, artillery and professional officers.

We see the same story repeated time after time in the history of revolutions. How did the barefoot volunteers of the Convention defeat the armies of royalist Europe? How did the untrained American militias hold in check the mercenaries of King George? How did the Bolshevik Red Army defeat the 21 armies of foreign intervention in 1917-20? In every case, the revolutionary armies prevailed because they were inspired by a burning desire to sacrifice everything – including their lives ‑ for the cause of the revolution. By contrast the apparently formidable armies of the old regime were armies of hired mercenaries or slaves compelled to fight for something they did not believe in.

The agrarian revolution could have been the basis for a complete social overturn in Mexico, on the lines of the Bolshevik revolution of 1917. But there was a difference with Russia: the absence of a Bolshevik Party, like the party that under the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky led the Russian workers and peasants to power in November 1917.Unlike Russia, the Mexican peasants failed to find a revolutionary leadership in the towns in the form of the proletariat under the guidance of a Leninist Party. Thus, all the heroism and sacrifice of the peasants merely served as a stepping stone upon which the Mexican bourgeoisie raised itself to power. But once having installed itself in the Presidential Palace, the bourgeoisie began to prepare the betrayal of its peasant allies.

The upper stratum of the Mexican bourgeoisie was alarmed that the revolutionary movement of the masses was getting out of control. They feared (correctly) that the revolutionary solution of the land question could be the starting point of an all-out assault on private property itself. They therefore decided to put a stop to it. Their first act was to get rid of the most courageous leader of the revolutionary peasants. In 1919, Zapata was assassinated by Jesus Guajardo acting under orders from General Pablo Gonzalez. The murder of the peasant leader was a clear indication of the counterrevolutionary character of the Carranza regime.

Bonapartism

What happened next cruelly exposes the limitations of a purely peasant revolution. The murder of Zapata deprived the peasant movement of any possibility of developing into a coherent centralised force. Zapata had no party, and his removal was intended by the ruling class to disorganize and atomise the revolutionary movement in the countryside. It succeeded. The revolutionary movement splintered into many different factions. The fate of the peasantry – and the Mexican revolution – was to be decided elsewhere and by other class forces.

Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata After the death of Zapata the peasant movement, the motor force of the Revolution, suffered a decisive defeat at the hands of the bourgeois factions around Obregon and Carranza. Thereafter, the entire country degenerated into a state of chaos, with Pancho Villa’s forces rampaging through the north, and different factions fighting for control of the state. Isolated guerrilla units roamed across the country destroying and burning down many large haciendas and ranchos. At times, it was difficult to distinguish genuine revolutionary guerrillas from mere banditry.

Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata After the death of Zapata the peasant movement, the motor force of the Revolution, suffered a decisive defeat at the hands of the bourgeois factions around Obregon and Carranza. Thereafter, the entire country degenerated into a state of chaos, with Pancho Villa’s forces rampaging through the north, and different factions fighting for control of the state. Isolated guerrilla units roamed across the country destroying and burning down many large haciendas and ranchos. At times, it was difficult to distinguish genuine revolutionary guerrillas from mere banditry.

Society cannot exist in a state of permanent instability. The bourgeois yearned for “order”. The masses were exhausted and their leaders had no perspective. The unstable balance of forces was eventually settled by the victory of the bourgeois politician Venustiano Carranza, who, in 1917, took over the presidency and passed a new Constitution. The Constitution of 1917, which is still formally in effect today, marked the victory of the bourgeois democratic revolution in Mexico. Its central point was land reform, which, in the form of the ejido (farming cooperatives), carried out the redistribution of a large portion of the land held by the wealthy land holders to the peasants.

By this measure, the Mexican bourgeois succeeded in defusing the situation and demobilizing the peasant revolutionary armies. The peasants looked upon this as a victory. But it was the bourgeoisie that was the real victor. It succeeded in making itself master of the state. But in so doing, it had to be careful to appeal to the revolutionary instincts of the masses, both the peasants and, to a certain extent, the working class.

Just as the French Revolution ended in the rule of Napoleon Bonaparte, so the Mexican Revolution ended in a bourgeois regime with clear Bonapartist features. The bourgeoisie thus carried through a counterrevolution under the banner of the Revolution, which thus became an Institution. The PRI itself, the so-called Revolutionary Institutional Party, was a Bonapartist party, through which the Mexican bourgeoisie, having seized state power on the backs of a popular revolution, sought to disguise its class rule by skilfully balancing between the classes.

In a way that has few precedents in history, the bourgeoisie developed political deception and demagogy to a fine art. After Carranza, other leaders continued to carry out reforms, for example in education and land distribution. By skilfully manoeuvring between the classes, the bourgeoisie managed to achieve a degree of stability that was exceptional in Latin America and lasted for generations.

As the bastard child of the Mexican Revolution, the PRI, while representing the class interests of the national bourgeoisie, always had a left wing, which leaned on the workers and peasants to strike blows against imperialism. One of the most radical of these left leaders was General Cardenas, the man who invited Trotsky to take up residence in Mexico, when every other “democratic” government in the world had shut its doors against him. Cardenas was undoubtedly a genuine revolutionary democrat, who nationalized the Mexican oil industry in 1938.

Cardenas went very far in his policy of nationalisation, leaning on the revolutionary masses to strike blows against imperialism. He never ceased to be a bourgeois revolutionary, but he showed great courage in fighting imperialism, for which Trotsky expressed the warmest admiration. The heritage of Lazaro Cardenas provided the PRI with a solid base of support, which lasted for decades. It is the secret of the relative stability that Mexican capitalism enjoyed until recently. For seven decades the PRI ruled supreme, through a combination of cunning, corruption and carefully organised violence. But now all that is over. A new and turbulent period opens up for Mexico.

The heritage we defend

The 1910-20 revolution was a great leap forward for Mexico. It partly solved the agrarian question – although not entirely. It destroyed the power of the old corrupt oligarchy that had misruled Mexico for decades. It laid the basis for a further development of capitalism and industrialisation, and therefore for the creation of the mighty Mexican proletariat. But ultimately, the revolution remained incomplete, unfinished and botched.

Liberation Army of the South, which was led by Emiliano Zapata The reason for its failure was the absence of a strong revolutionary class in the urban centres, capable of providing a coherent leadership to the stormy and heroic movement of the revolutionary peasantry. The nascent movement of the Mexican proletariat was as yet in its infancy. Its immature and undeveloped state was reflected by the domination of the anarchists, who displayed their usual confusion in relation to the revolutionary-democratic movement.

Liberation Army of the South, which was led by Emiliano Zapata The reason for its failure was the absence of a strong revolutionary class in the urban centres, capable of providing a coherent leadership to the stormy and heroic movement of the revolutionary peasantry. The nascent movement of the Mexican proletariat was as yet in its infancy. Its immature and undeveloped state was reflected by the domination of the anarchists, who displayed their usual confusion in relation to the revolutionary-democratic movement.

One hundred years later, the situation is completely different. The majority of the population now lives in towns and cities. The specific weight of the proletariat is a thousand times greater. Together with the semi-proletarian masses and the urban and rural poor, the working class constitutes the decisive majority of society. Today the only class that really stands for the traditions of Zapata and the Mexican Revolution is the proletariat, which has potentially the power to transform society from top to bottom. But in order that this colossal potential should become reality, certain things are necessary.

In every modern society, the power of the working class is manifest. It is a necessary produce of modern industry and the relations of production that have been established by capitalism itself. In modern society, not a wheel turns, not a light bulb shines, not a telephone rings without the kind permission of the working class. This is a colossal power, but the workers do not realize that they possess such power.

Let us draw a parallel with nature. Steam, too, is an enormous power. It is the basis of the Industrial Revolution. But steam is only a power in reality, as opposed to a mere potential power, when it is harnessed and concentrated in one point – through a piston box. In the absence of this mechanism, steam will merely dissipate uselessly into the atmosphere. The political equivalent of a piston box is a revolutionary party with a revolutionary leadership.

Mass movement in Mexico City against electoral fraud in 2006 This proposition can be shown from recent Mexican history. The immense power of the working class was seen in the mass movement of 2006. Those events brought forcefully to the fore the central importance of leadership. The Mexican ruling class, and its pay masters in Washington, were terrified of the victory of Lopez Obrador, the left-wing PRD candidate. They therefore took steps to rig the elections.

Mass movement in Mexico City against electoral fraud in 2006 This proposition can be shown from recent Mexican history. The immense power of the working class was seen in the mass movement of 2006. Those events brought forcefully to the fore the central importance of leadership. The Mexican ruling class, and its pay masters in Washington, were terrified of the victory of Lopez Obrador, the left-wing PRD candidate. They therefore took steps to rig the elections.

As everybody knows, there is nothing new in this. It would be a difficult task to point to an election in Mexico that was not rigged! Yet this time it was different. Millions of Mexicans came out onto the streets to protest against electoral fraud. They camped on the Zocalo and refused to leave, defying all the attempts of the authorities to move them. This magnificent movement of the masses had the potential to lead to a genuinely revolutionary movement.

All that was required was to call a general strike, set up democratically elected action committees of workers, peasants, unemployed, women and youth, and the way would have been open for the transfer of power to the workers and peasants. But this was not done, the energies of the masses gradually evaporated like steam in the atmosphere, and the opportunity was lost.

However, that is not the end of the story. The Calderon government cannot do what the bourgeoisie did in the past. The crisis of capitalism means it has no room for manoeuvre. It is compelled to attack the living standards and rights of the Mexican people. That is the reason for the brutal attack on the electricians’ trade union. But the Mexican workers will not remain with their arms folded while the bankers and capitalists destroy all they have won in the past. The stage is set for new and violent class struggles that will put the events of the first Mexican Revolution in the shade.

A new Mexican Revolution – the Socialist Revolution – is being prepared. This will have an impact that is a thousand times greater than the first Mexican Revolution. It will send shock waves through all Central and South America, provoking a revolutionary upsurge everywhere. The effects of a proletarian revolution in Mexico will not halt at the Rio Grande.

Long ago, Porfirio Diaz uttered the celebrated phrase: “Poor Mexico, so far from God, so near to the United States.” But the remorseless dialectic of history has turned this relation on its head. American imperialism, which for a long time exploited and oppressed Mexico and the rest of Latin America, now lives in fear of the revolutionary wave that is sweeping the Continent. All the efforts of the most powerful state in the world to erect barriers to prevent human beings from entering its territory will be powerless to prevent the influx of revolutionary ideas.

The global crisis of capitalism is hitting the United States hard. For millions of people, the American dream has become the American nightmare. Washington is constantly conspiring against the government of Hugo Chavez because it understands that the Venezuelan Revolution is a point of reference for the revolutionary movement throughout Latin America. They conspired to prevent Lopez Obrador from winning the elections in 2006 because they did not want another Chavez (as they believed him to be) on their doorstep.

The fears of US imperialism are well grounded. Today the Hispanic population of the USA has overtaken the Afro-Americans as the biggest ethnic minority. It is overwhelmingly composed of the most poorly paid and exploited sections of society. The recent mass mobilisations of migrant workers in the USA revealed a considerable revolutionary potential. A revolution in Mexico would be the spark that ignites the powder keg. It would spread rapidly through US society, posing the question of a fundamental social and political change in the most powerful capitalist nation on earth.

The Mexican Revolution was, in reality, only the first instalment. It was a glorious anticipation that pointed the way forward. It shook Mexican society out of its lethargy and prepared a great cultural revolution. The achievements of Mexican music, art and literature are justly celebrated, as is the work of Mexican anthropology, architecture and science. The names of Diego Rivera, Orozco, Ponce, Revueltas are internationally renowned. These are all the children of the Mexican Revolution, and would be unthinkable without it.

If the bourgeois revolution in Mexico had such profound effects, one can scarcely imagine what the impact of the coming socialist revolution would be. A socialist plan of production would awaken all the colossal potential of the Mexican people. It would mobilise the vast productive and cultural potential of this great land and produce a cultural, artistic and scientific revolution such as the world has never seen. For us, the Mexican Revolution is not a distant memory of the past. It is a glimpse of the future – a future full of hope and inspiration for the people of Mexico and the entire world.

London, July 14, 2010