The two-month long series of congressional assemblies of the PSUV in Venezuela recently came to an end. The debates in the congress clearly indicate that a left-right polarisation is taking place within the party, with the rank and file seeking a revolutionary way out and a right-wing bureaucracy that is trying to mould the party to its own outlook.

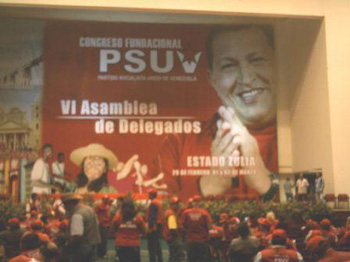

The PSUV (United Socialist Party of Venezuela) has just concluded its two-month congress period. As we reported earlier, this is an event of historic importance. Approximately 1800 delegates representing a total of 5.6 million people who registered to join have gathered at the weekends since the beginning of January to discuss the crucial issues facing the Venezuelan revolution; what kind of programme, methods, ideology and organization are required in order to complete the revolution and move towards Socialism.

As the congress came to an end on Sunday, March 2, the delegates returned to their home regions in order to continue the work and put the decisions of the congress into practice. The following Sunday, March 9, the national leadership of the PSUV was elected.

Here we draw a first balance sheet of the events and outline the necessary conclusions. We must analyse carefully the decisions, debates and mood at the congress and understand all this as part of the ongoing revolutionary process in Venezuela.

Congress in a revolutionary context

An essential part of our analysis is that we take the revolutionary situation that exists in Venezuela as our starting point. If we fail to understand the Venezuelan revolution and what phase it is passing through, we will be completely incapable of understanding the contradictions that emerged during the congress and the significance of the different polemics and discussions that took place within it.

The PSUV congress has not been taking place in a "normal" situation. In most European countries the congresses of the traditional Socialist or Communist parties are smoke-screens, a theatre which is intended to "calm" the rank and file and where most results are decided beforehand by the bureaucratic clique of parliamentarians, full-time functionaries and so on. These congresses usually bear more resemblance to a media-show that the party-tops use to get free PR than an actual exercise in political discussions and democratic decision-making.

The PSUV congress has not been taking place in a "normal" situation. In most European countries the congresses of the traditional Socialist or Communist parties are smoke-screens, a theatre which is intended to "calm" the rank and file and where most results are decided beforehand by the bureaucratic clique of parliamentarians, full-time functionaries and so on. These congresses usually bear more resemblance to a media-show that the party-tops use to get free PR than an actual exercise in political discussions and democratic decision-making.

In Venezuela things are very different. Not because everything is perfect and is moving in a straight line. As we will demonstrate, a bureaucracy is also beginning to emerge within the PSUV that will - if it is not stopped in time - go on to destroy the revolution from within. However, the main point now is that this bureaucracy is still not in a position where it can do what it likes with the party. Why is that? Because in Venezuela, there is an extraordinary revolutionary situation that is driving millions of workers, youth, peasants, intellectuals and urban poor into action.

As Trotsky explained, a revolution is a process where the masses enter the arena of politics and take their destiny into their own hands. It is this tremendous pressure from below that is being channelled into the PSUV and which was reflected in the congress. The very fact that the PSUV is being created is the result of the discrediting of the old Bolivarian parties and the demand from the revolutionary masses for genuine democracy within the movement, a demand which is directed against the unelected right wing that dominates at the top. Chávez was sensitive to this and proposed the formation of the PSUV as a way of giving power to the rank and file. This is also reflected in the way that the congress was organised: over two months of discussions, delegates elected by the rank and file with the right of recall and in many places weekly assemblies in the home regions where the delegates reported back to the rank and file and discussed with them the issues, a process of discussion which involved hundreds of thousands if not millions of people. The Bolivarian bureaucracy was clearly not happy with this state of affairs, a product of the enormous pressure from below, and tried at every stage to water down and limit the power of the rank and file and the delegates.

Militant mood among delegates

One feature dominated the congress and prevailed in all the sessions and debates: the struggle between, on the one hand the majority of delegates, most of them honest revolutionaries, natural leaders from poor Chavista neighbourhoods, student movements or trade unions, who are trying to build the PSUV as the party that the revolution needs in order to win the decisive victory, and on the other hand a small reformist bureaucracy trying to impose its will and convert the PSUV into a repetition of the MVR, Chávez's former party, which was rightly regarded as no more than a bureaucratic electoral machine, full of careerists, bureaucrats, infiltrated right wingers and corrupt professional "politicians".

Again and again, we saw how the majority of the delegates reflected the aspirations of the rank and file to build the party on genuine revolutionary lines. This was for example the case, when during the third session, celebrated in Puerto Ordaz, in the Bolivar region, the delegates from Caracas proposed that the term "anti-capitalism" should be included in the Declaration of Principles. The bureaucracy (and also the Communist Party) argued that "anti-capitalism" was already implicit in the definition of the party as socialist. But the delegates insisted on including the term which forced the bureaucracy to postpone the voting on this document. During the fourth session of the congress, in Caracas, Jorge Rodriguez said that the party had already voted the Declaration of Principles but he was heckled by the delegates who reminded him that this was not the case. This was seen as an attempt to avoid the issue and resulted in "anti-capitalism" finally being included in the text.

Again and again, we saw how the majority of the delegates reflected the aspirations of the rank and file to build the party on genuine revolutionary lines. This was for example the case, when during the third session, celebrated in Puerto Ordaz, in the Bolivar region, the delegates from Caracas proposed that the term "anti-capitalism" should be included in the Declaration of Principles. The bureaucracy (and also the Communist Party) argued that "anti-capitalism" was already implicit in the definition of the party as socialist. But the delegates insisted on including the term which forced the bureaucracy to postpone the voting on this document. During the fourth session of the congress, in Caracas, Jorge Rodriguez said that the party had already voted the Declaration of Principles but he was heckled by the delegates who reminded him that this was not the case. This was seen as an attempt to avoid the issue and resulted in "anti-capitalism" finally being included in the text.

During the same third session, we also saw how the proposal to organise street demonstrations at each plenary session was adopted and the delegates organised an anti-imperialist rally in Puerto Ordaz, and were joined by hundreds of workers from the nearby giant steel mill SIDOR who, as part of the collective bargaining struggle, are demanding the nationalization of the company.

As we reported previously, a big part of the delegates during the last three assemblies of the congress showed a keen interest in Marxist ideas and the comrades of the CMR sold Marxist books and pamphlets worth more than 4000BF (nearly 1000 euros) and more than 350 copies of the paper El Militante. This is of course only one indicator, but if we view it together with the discussions in the congress, it constitutes a clear signal: significant sectors of the delegates are searching for revolutionary Marxist ideas.

Programme and Declaration of Principles

The pressure from below left its mark on many of the main decisions of the founding congress. This can be seen most clearly in the new Declaration of Principles. The programme of the PSUV was voted as a draft, which will then be discussed and edited in a special "ideological congress" which is set to take place after the elections of governors and mayors in November. In our previous report we analysed some of the contradictions in this document.

However, the "Declaration of Principles" which is the other document approved, is much clearer and firmer in its positions. It includes, among other things, the need to expropriate the Capitalists who own the means of production:

"The inefficiency in the exercise of public power, bureaucratism, the low level of participation of the people in the control and management of government, corruption and a widening gap between the people and government, threaten [to undermine] the trust that the people have placed in the Bolivarian revolution." (...)

"The interests of the private sector in the production and distribution of goods and services, whose speculative interests are derived from their control over the ownership of the means of production, are a further threat to the Bolivarian revolution. In the case of food, it is not enough to fight against sabotage and lack of supply with administrative measures. What is required is a strategic perspective of entrusting the property of the means of production to the organised people".

There is also a highly significant paragraph about the ideological foundations of the party:

"The party will take as its starting point the tree of the three roots: the thinking and actions of Simón Bolivar, Simón Rodriguez and Ezequiel Zamora. It will strive to educate its members and militants, adopting as a guide the thinking and actions of revolutionaries and socialists from all over the world like José Martí, Ernesto Che Guevara, José Carlos Mariátegui, Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, Lenin, Trotsky, Gramsci and others who have made contributions to the struggle for social transformation"

The pernicious role of the reformist bureaucracy: The Táscon affair

Of course, this is only one side of the coin. In spite of all this progress, which is clearly the product of the pressure from below, the right wing inside the Bolivarian movement also managed to put their stamp on the congress proceedings.

But what right wing are we talking about? We are referring here to those elements inside the movement that are trying to slow down the revolution and eventually reach some kind of agreement with the opposition and with imperialism. In a desperate attempt to put a check on the revolution, these people have been promoting the idea of a "socialism which includes different forms of property". With this slogan they want to put a stop to the nationalisations and defend private ownership of the means of production. These are ideas that have been given a "theoretical" cover by the well-known reformist writer Heinz Dietrich.

These people have installed themselves in key positions within the state-apparatus and from these positions they sabotaged the referendum campaign in December, thus helping the opposition to win a narrow victory. In the PSUV they are trying by all means possible to introduce reformist ideas and control the party from above.

This right wing is most commonly identified with Diosdado Cabello, a wealthy businessman who is now governor of the state of Miranda. Throughout the congress, Cabello was part of the "technical support committee" which organized the congress and its sessions.

The first big clash between this bureaucratic right wing and the aspirations of the majority of the delegates, representing the revolutionary rank and file, took place at the fourth assembly, held in Caracas from February 15 to 18.

The immediate cause of this conflict was the fact that Luís Tascón, a member of parliament and member of the PSUV, came out in the open, accusing the brother of Diosdado Cabello, José David Cabello who was recently appointed as the head of SENIAT, the Venezuelan tax revenue office, of corruption and irregularities in relation to the purchase of 4-wheel drive vehicles and coaches. He even went to the length of bringing the case up in the media, including Globovision, the right-wing oppositionist TV-channel. Faced with this, Diosdado Cabello launched a vicious attack against Tascón, who he accused of being "an agent of the Empire" and proposed that he should be expelled from the PSUV. Chávez himself came out in defence of Cabello and also attacked Tascón publicly.

On Saturday, February 16, Jorge Rodríguez, former vice-president who is now the leader of the provisional PSUV leadership, appeared on national television together with Diosdado Cabello and announced that "Tascón had been expelled for lack of discipline by the congress with a unanimous majority"(!). This was a blatant lie, and the reaction of the rank and file was immediate. In Caracas the delegates demanded that Jorge Rodríguez should come to a meeting and explain his actions.

Regardless of the methods of Tascón and the way in which he launched the corruption charges, it is absolutely impermissible to expel someone from a party that has not even been formed. How can an un-elected leadership expel someone by decree? And why do the un-elected leaders lie about decisions in the media, while accusing the expelled of "lack of discipline"? What should have been done was to open an investigation on Tascón's accusations and then have a democratic discussion in the party ranks about the case.

As a congress delegate at the congress pointed out the following day: "He is an opportunist and should not have gone to Globovisión, but who are Jorge Rodriguez and Diosdado to expel him and then to say that this was decided by the party? These are IV Republic methods and we will not allow them".

Faced with the anger of the delegates and the rank and file, Jorge Rodríguez had to take half a step backwards and said that Tascón will have the opportunity to defend himself against the expulsion charges.

Elections for leadership

The second big clash between the left and the right took place during the discussions on how to elect the national leadership of the PSUV. In a revolution, the masses are very sensitive to democratic issues. They demand that the party must be controlled democratically by the rank and file, and that the leaders be subject to the right of recall. They view this as the only guarantee for a genuine Socialist policy. Chávez himself had repeatedly stated that the PSUV was going to be the most democratic party in the history of Venezuela.

As no agreement on the method of electing the leadership could be reached in the congress, the reformists proposed that Chávez himself should name 69 candidates that could then be presented for elections to the more than 80,000 voceros and commisionados, elected representatives of the PSUV battalions [party branches]. This provoked a big sense of distrust and anger among a number of delegates who rightly feared that this would give the right-wing reformists control of the party leadership.

In the end no compromise was reached, so Jorge Rodríguez took everyone by surprise in the fifth assembly of the delegates in Puerto la Cruz, in the State of Anzoátegui, where he suddenly declared that each delegate should write three names on a sheet of paper and then all the ballots would be taken to Miraflores presidential palace where Chávez would name the 69 candidates, taking the wishes of the delegates into account. But according to Jorge Rodríguez these three names could not be anyone, only "recognized leaders".

In the end no compromise was reached, so Jorge Rodríguez took everyone by surprise in the fifth assembly of the delegates in Puerto la Cruz, in the State of Anzoátegui, where he suddenly declared that each delegate should write three names on a sheet of paper and then all the ballots would be taken to Miraflores presidential palace where Chávez would name the 69 candidates, taking the wishes of the delegates into account. But according to Jorge Rodríguez these three names could not be anyone, only "recognized leaders".

The bureaucracy had to use the enormous personal authority Chávez has in the movement in order to impose this method. Taking the ballots to Miraflores prevented the delegates from knowing how many votes each of the candidates had received. Forcing them to name three candidates there and then prevented them from consulting with the rank and file and also prevented prospective candidates from presenting themselves and their ideas to the delegates, etc.

In a letter to Chávez, dated March 8, a significant number of delegates (according to the Venezuelan website Aporrea between 33% and 40%), stressed that this process of electing the PSUV leadership has suffered various violations of what they conceive as basic principles of revolutionary rank-and-file democracy.

In our opinion, this method used to select the candidates for the leadership opened the door for the moderate, reformist elements and politicians to get a greater representation within the leadership. In the list of the 69 candidates, of which 15 were elected on Sunday, March 9, there were a large number of people who were previously in the discredited leadership of the MVR. Although some of the names, such as Freddy Acevedo, a young Marxist and student activist from Táchira, are genuine fighters, there are also a lot of people who are seen by the masses as useless bureaucrats. Significantly there is only one trade unionist among the 69.

In the end, on March 9, the vote took place and 15 full members and 15 alternate members of the leadership were elected. During the week lots of discussions took place and for the first time, with all its limitations, there was a clear, open and public left-right demarcation within the leadership of the Bolivarian movement. It is quite significant that once the results were counted Diosdado Cabello did not make it onto the list of 15 full members (although he came first among the alternates). A number of prominent figures who were identified as right-wingers were not elected as full members (Caracas mayor Freddy Bernal, Lara governor Luís Reyes Reyes, oil minister Rafael Ramirez, William Lara, Darío Vivas, Rafael Isea) and some did not make it onto the leadership at all (opportunist turn-coat Francisco Arias Cárdenas, Rodolfo Sanz, Jesse Chacón, etc). So while the result is a mixed one and the new leadership includes a majority of right-wing reformists but also some who are identified as left-wingers, the fact that the main figure of the right wing, who was prominent during the congress, Diosdado Cabello, received such a low number of votes, despite having at his disposal a well-oiled political machine, is a clear reflection of the strength of the mood of the rank and file.

The role of Chávez

The role of Chávez in all this has been very ambiguous and contradictory. At times he has attacked what he calls "splitting elements" and called for "unity and discipline" inside PSUV. In one of his speeches in the congress he also went on to defend Diosdado Cabello against political attacks from the left. He proposed the expulsion of Táscon and pushed heavily for this to be carried out. Furthermore he used his authority to get the method of election to the leadership approved. This disappointed a number of delegates and rank-and-file members who thought that Chávez would support the left in the struggle against the bureaucracy.

But at the same time he has attacked ideas promoted by the right wing such as "Chavismo without Chávez". While nominating people from the bureaucracy he has also nominated people identified with the left. This is for example the case with the former general Alberto Müller Rojas. Previously, in the summer of 2007, Chávez had a public polemic with Müller Rojas over the question of whether soldiers and officials in the army could be part of the PSUV (see The challenges facing the Venezuelan Revolution). At that time Müller Rojas argued for military officers to join the PSUV whereas Baduel (who later passed over to the side of the counter-revolution in November 2007), opposed it. At that time Chávez supported Baduel and Müller Rojas was removed from the PSUV promoting committee. But at the closing session of the PSUV congress on Sunday, March 2, Chávez proposed that Müller Rojas should be the vice-president of the PSUV!

This is quite typical of the vacillations of Chávez. His somersaults are not only reflected in different political ideas but also in the choice of individuals. Chávez is without doubt an honest individual. But he doesn't have a clear idea of how to advance and tackle the difficulties that the situation presents. By not taking any decisive measures against the bureaucracy and by keeping his destiny tied to individuals who are clearly part of the reformist bureaucracy he is undermining his own base of support within the revolutionary movement.

As an experienced military man, Chávez sees unity as the guarantee for the future. But the decisive question is this: Is it possible to obtain unity between the views of the right and the left, that is to say, between reformism and revolution?

How to fight the bureaucracy - the need for a left opposition

Although the first battles within the PSUV may appear as merely organizational issues, at bottom they reflect a political struggle. The main problem is that the majority of the delegates who are seeking a revolutionary road are not organized. The minority in the congress, the reformist bureaucracy, is very well organized and works in a coordinated and conscious manner. This explains why they were able to win several victories in the congress in the face of strong opposition.

Faced with this fact, what conclusion should the revolutionaries draw? We should call for the organisation of a left current, with a clear platform of revolutionary socialist policies. We should demand that the organizational methods correspond to the political objectives set out in the Declaration of Principles. If the PSUV is supposed to be the instrument with which to abolish capitalism in Venezuela, the party should be organized in a way that favours this end.

Faced with this fact, what conclusion should the revolutionaries draw? We should call for the organisation of a left current, with a clear platform of revolutionary socialist policies. We should demand that the organizational methods correspond to the political objectives set out in the Declaration of Principles. If the PSUV is supposed to be the instrument with which to abolish capitalism in Venezuela, the party should be organized in a way that favours this end.

The question is this: how do we fight effectively against the bureaucracy? It is not possible to defeat the bureaucracy by raising purely organizational questions and polemics. We must attack the bureaucracy at its weakest link: its reformist and conciliatory policies. We must expose these policies and show that they will lead the party and the revolution to disaster.

Only two roads: reform or revolution

To both the left reformists and the sectarians the struggles inside the PSUV will come as a huge surprise. They thought that after the defeat in the constitutional referendum the masses were demoralised and that this was the beginning of a lull in the revolutionary movement in Venezuela. As on so many other occasions, they have proved themselves incapable of understanding the perspectives for Venezuela and how the Bolivarian masses move.

The convulsions that we witnessed at the PSUV congress did not come as a surprise to the Marxists. After the referendum defeat, we pointed out the following, in an article written on December 3 by Alan Woods:

"The victory of the ‘no' in the referendum will act as a salutary shock. The Chavista rank and file are furious and point the finger at the bureaucracy, which they rightly blame for the setback. They are demanding action to purge the right wing from the Movement."

(Venezuela: The referendum defeat - What does it mean?)

This is precisely what is happening today. This and this alone explains the polemics and conflicts within the congress. The revolutionary pressure from below put its mark on many results of the founding congress, most notably on the Declaration of Principles. On the other hand, the bureaucracy managed to get control of the national leadership. But it would be completely wrong to think that the masses will let the bureaucracy keep its grip over the party intact without a fight. The masses will try again and again to re-conquer the party and challenge the bureaucracy.

The scene is set for a ferocious battle between the revolutionary rank and file and the bureaucracy. Any attempt at a compromise will prove futile; reformism and revolution are like water and fire - impossible to mix together. In the coming weeks there will be a number of debates within the PSUV rank and file and thousands of activists in the vanguard will begin to draw conclusions. A national gathering of left-wing PSUV delegates has been called on April 5, which is co-sponsored by the Revolutionary Marxist Current (CMR). This will be an important event in discussing the lessons of the congress and organizing the future work of the left inside the PSUV.

The latest provocation of imperialism with the violation of Ecuadorian territory by Colombian troops is a clear warning to the Venezuelan revolution: US imperialism is still keeping a vigilant eye on Venezuela, ready to take whatever chance may crop up to strangle the revolution. But this time they would use the moderate elements within chavismo and within the PSUV, as a fifth column that can make this task easier.

The Venezuelan revolution finds itself at a crossroads. The newly founded PSUV will have to face a variety of problems: the ongoing economic sabotage that is provoking frequent scarcity of basic food products, the speculation of the capitalists that is pushing up inflation, the lack of cheap housing, the need to tale up the popular demand for measures against the coup-plotting TV-station Globovision, among others.

After nearly ten years of revolution, a dozen of elections, constant mobilisations and countless speeches about Socialism and revolution, the masses are beginning to question the pace of events. Not because they are tired of Socialism, but because they are tired of endless speeches, words, phrases without any decisive action being taken. It is in this context that reformism and revolution face each other in such an irreconcilable manner.

March 10, 2008

See also:

- Venezuelan Marxists intervene in fourth assembly of the PSUV congress by José Antonio Hernández and Patrick Larsen (CMR Caracas) (February 21, 2008)

- Venezuela: The PSUV congress – what is at stake? by Patrick Larsen (February 5, 2008)

- Venezuela: the struggle against food sabotage begins, now expropriate the monopolies! by Jorge Martin (February 4, 2008)

- Interview with William Sanabria and Yonie Moreno (CMR) by Der Funke (February 4, 2008)