2023 saw the 100th anniversary of the birth of Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s first prime minister, and the man at the heart of the state today. The anniversary was marked by a torrent of remembrances of the figure once described by Henry Kissinger as “one of the asymmetries of history.” Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong (Lee Kuan Yew’s son) is stepping down on 15 May and passing the baton to a new generation of leadership unrelated to the Lee family. The continuation of Lee’s People’s Action Party and the entire edifice of the Singaporean state hangs in the balance. Therefore, it is important for Marxists and communists to understand the nature of the Singaporean state today.

The official propaganda of the Singaporean state is that the elder Lee, through his determination, competence and leadership, instilled a sort of civic patriotism in the Singaporean population, the spirit of which transcended all class conflict and marks Singapore as an “exceptional nation” to this day. However, to truly understand not only Singapore’s past course of development but also where it is going, we must pierce the veil of official propaganda and understand the real material conditions that laid the foundation for the country’s class-concilliationist politics. We must pay particular attention to the political formations that arose in the 1950s and 60s that moulded the Singaporean state into what it is today, and the market forces that shaped its development thereafter.

Singapore’s early development

Singapore is a small island at the tip of the Malay peninsula, the geography of which prevented large-scale agricultural societies from developing. Hence, before British colonisation, the only established urban centre was a small fishing and trading port. This port was seized upon and expanded significantly by Sir Stamford Raffles on behalf of the British, to counter Dutch trading dominance in the region.

The vast entrepot trade that flowed through Singapore’s harbour under British rule stimulated the development of a largely ethnically Chinese merchant class that acted as compradors for European traders in the region. As the port grew and adjacent industries were developed to support it, a sizable working class of mostly Chinese but also Indian and Malay descent developed alongside it.

Who was Lee Kuan Yew?

Understanding Lee not as an “enlightened administrator” but as a representative of the Singaporean petty-bourgeoisie, helps explain his ideas and the role he played in the events to come / Image: Wellington City Archives collection, Wikimedia Commons

Understanding Lee not as an “enlightened administrator” but as a representative of the Singaporean petty-bourgeoisie, helps explain his ideas and the role he played in the events to come / Image: Wellington City Archives collection, Wikimedia Commons

Harry Lee Kuan Yew was born on 16 September 1923, to a wealthy Peranakans (Straits Chinese) family during British colonial rule. He was the eldest of five children of a Shell Oil Company depot manager. Lee was fast-tracked to receive tutelage at the prestigious Raffles Institution, giving him access to a university education at the London School of Economics and later Cambridge.

This background is not secondary as it shaped Lee’s ideology and class outlook. Understanding Lee not as an “enlightened administrator” but as a representative of the Singaporean petty-bourgeoisie, trained in the worldview of the British ruling class, helps explain his ideas and the role he played in the events to come.

Retreat of British imperialism

Though victorious in the Second World War, British imperialism was extremely weakened and a series of mutinies in the army forced them to recognise that they had to relinquish direct control of their colonial possessions in South East Asia. However, due to its strategic location as a trade hub, the British took extreme precautions to ensure Singapore would not slip out of their hands politically or economically.

As Trotsky remarked in a speech in 1926:

“Singapore and Hong Kong mark the most important highways of imperialism. Singapore is the key between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific. It represents one of the most important bases of British policy in the Far East.”

Maintaining that control would not prove so easy in the tumultuous period following the Second World War, with the Soviet Union emerging as a major power, and the Chinese Revolution providing a beacon to the workers and oppressed in South East Asia. The question of Singapore’s formal independence was inevitable, the question was: what class would lead it?

To ensure governance could be passed to a responsible bourgeois party, while maintaining a loyal opposition, the British extended a prolonged period of transition to independence beginning in 1948, in which year after year more seats of the Legislative Council went up for election. The idea was that this would create an environment in which a two-party system - as existed in Britain - could develop, which would be easy to keep under British influence.

However, due to the nature of Singapore’s development as a colonial trading hub, the tiny local bourgeoisie was tied hand and foot to British capital, and had no interest in leading the independence movement or fostering a national consciousness. Hence, the Singaporean bourgeois surprised even the British with their ineptitude. The political parties they put up, like the Singapore Progressive Party, never had any appeal outside of their narrow merchant interest groups.

Additionally, the resistance against the Japanese occupation of Singapore during World War II was led almost entirely by the armed regiments of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), as British and bourgeois elements collaborated with the Japanese occupation forces, discrediting themselves in the eyes of the working class.

The Singaporean working class was highly organised in the Singapore Federation of Trade Unions (SFTU), which was under MCP control, and on many occasions undertook militant strike action against the poverty and exploitation of the colonial system. Singaporean workers looked to the anticolonial revolutions sweeping the region, and especially the Chinese revolution, as a solution. Resisting this revolutionary pressure, and cracking down on any subversion was, therefore, the top priority of the British administration.

Lee’s plan for a mass party

This was the landscape that Lee entered when he returned to Singapore in 1950. He began working for a law firm, which gave him a front-row seat in the unfolding class struggle. It was through this that he became convinced of the inability of the Singaporean bourgeoisie to create a mass base for a bourgeois nationalist party. Lee, more than any of the other petty-bourgeois intellectuals in his circles, realised that this mass base could only be brought about by co-opting the trade union and labour movement.

Lee sought to make a name for himself as a champion of the workers and the oppressed by taking on cases against the British authorities, often pro bono. It was through this work that he was introduced to Lim Chin Siong and Fong Swee Suan, leaders of the influential bus drivers’ and factory unions. While the unions were strongly influenced by communists, Lee consciously sought their support as he believed he could use them, simultaneously convincing the British authorities that he could keep the communist elements at bay. The ‘lefts’ in turn believed that an alliance with these ‘respectable’ petty-bourgeois elements would protect them from being proscribed and imprisoned.

It is very clear that, while publicly Lee touted his left-wing or working-class sympathies, he at all times knew what class interests he was really defending. Already before coming to Singapore Lee gave the following address to the Malayan Forum in London:

“. . . If we, who can become the most privileged part of the local population under British rule, openly declare that British imperialism must go, the effect will be immediate. But if we do not give leadership, it will come from the other ranks of society, and if these leaders attain power, as they will with the support of the masses, we shall find that we, as a class, have merely changed masters… [But] our trump-card is that responsible British leaders realise that independence must and will come to Malaya and that therefore, it will be better to hand Malaya to leaders sympathetic to the British Commonwealth, and what is more important, willing to remain in the sterling area.”

Lee certainly understood the tasks facing the Singaporean bourgeoisie. Furthermore, his gambit worked and he won over Lim, Fong and other left-wing elements to his coalition, which culminated in the founding of the People’s Action Party (PAP) on 21 November 1954.

The students fought back with school sit-ins and mass demonstrations in which workers also participated / Image: The National Archives UK, Flickr

The students fought back with school sit-ins and mass demonstrations in which workers also participated / Image: The National Archives UK, Flickr

With both a respectable middle-class leadership that was palatable to the British, as well as a mass working-class base provided by the trade unions, the mixed-class nature of the PAP proved a winning formula in the parliamentary arena. The party quickly made large inroads into the Singaporean working class by outwardly advancing strong anti-colonial and socialist messaging. However, within the party, the Lee wing was conspiring to shore up more and more control of the executive and limit the control of the local branches.

The left-wing went on the counter-offensive, winning four of the 12 central executive committee seats and attempting to push through changes to the PAP constitution that would enshrine more rank-and-file democracy in the party. This was a serious threat to the petty-bourgeois leadership group around Lee as it might actually make the party beholden to its working-class base.

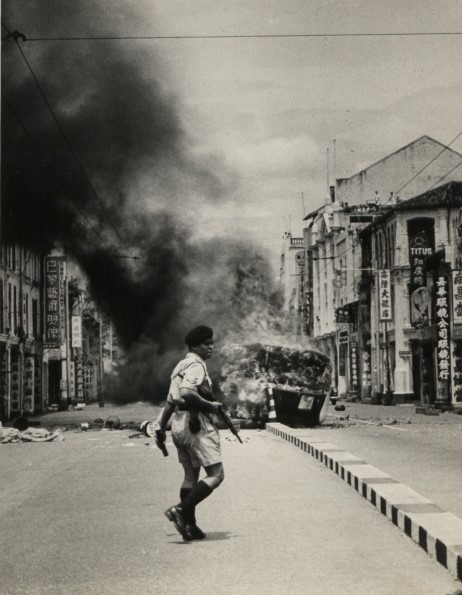

Fortunately for him, Lee’s group had considerable help in their battle against the left and party democracy. Under an internal security plan named ‘Operation Photo’ the British authorities began cracking down on cultural and social organisations by which the anticolonial movement was led. Particularly the organisations of the Chinese working class and youth were targeted. The Singapore Chinese Middle School Student Union was banned and two schools were closed. The students fought back with school sit-ins and mass demonstrations in which workers also participated. The police attacked the students and the situation escalated into what is now known as the Chinese Middle School riots, in which 15 people died. This escalation provided the political pretext for the arrest of almost the entirety of the leadership of the left, which included three of the four recently elected to the PAP CEC.

Lee used this opportunity to consolidate his position, and made sure none of the ‘lefts’ were part of the delegation to London to negotiate the extension of independence to Singapore. With the British satisfied that the communist threat had been dealt with, it was agreed that Singaporean independence would be achieved via a merger with the Federation of Malaya, and governance handed over to an Internal Security Council (ISC) with wide-ranging powers of arbitrary arrest and detention.

Developing capitalism with bonapartist characteristics

With the left suppressed, the PAP came to power based on a “transitional plan,” the core of which was a heavy emphasis on developing industry that could compete on the world market and solve the serious unemployment that plagued the island. However, based on capitalism, this industrialisation plan was dependent on there being a common market with Malaya, as well as sufficient capital and technical know-how to bring Singaporean industry up to a level where it could compete globally.

The PAP consulted the help of the World Bank to develop a plan for Singapore’s industrialisation, and they published their findings in what became known as the Winsemius Report. The report concluded that, even with the presumed precondition of the merger with Malaya, the driving force of Singapore’s industrialisation would have to be foreign capital, and hence the need to seduce foreign capital would dictate the PAP's policy while in power.

Fortunately for them, the crushing of the workers' movement in the previous period had indeed created the political preconditions for foreign capital to feel confident investing in Singapore under the guiding hand of Lee’s PAP. This, combined with the huge surge in primary commodity prices during the Korean War and later the Vietnam War, allowed Singapore to industrialise and ride the postwar boom, providing to a standard of living considerably higher than many of its neighbouring countries.

The PAP skillfully combined repression with a welfare state that provided access to government-subsidised housing, healthcare and education, which insulated Singaporean workers from the negative impacts of rapid industrialisation and urbanisation. Furthermore, in large part due to the resulting class peace, the PAP was able to structurally readjust Singapore’s economy around the extension of globalisation, financialisation and the entry of China into the world market to become the key trading and financial hub in the region. This whole process has heavily distorted class relations within Singapore. The PAP facilitated this process, dissolving the trade unions and all other independent working-class organisations into the Singaporean state in what is known as the “tripartite model.”

With authoritarian methods, combined with social concessions and cynical nationalist propaganda, the PAP regime shored up passive support from among Singaporean workers for decades, and ensured that it was impossible for discontent to express itself through any channels outside of PAP control. In 1960 the party introduced the Internal Security Act, which gave itself sweeping police powers to “preventatively” detain and imprison any dissidents, especially communists. Critics of the state deemed “out of line” would often face lawsuits that left them in financial ruin. Opposition parties are allowed, but are rendered so anemic that they have virtually no hope of ever going into government. As a result, Singapore is de facto a single-party state under the PAP.

The Singaporean state after Lee

The future of the PAP, however, is anything but certain. The global crisis of overproduction, and the intensification of market penetration by competing world powers, are creating enormous turmoil. All of this serves to undermine the very foundations of Singapore’s prosperity and stability. The PAP only managed to consolidate its rule because of the extremely anomalous conditions of the postwar boom, which allowed for the extension of trade and commerce to undercut the class struggle for a certain period. These conditions are a thing of the past. The PAP cannot govern as it did, and many bourgeois commentators are worried about how it will manage the transition.

There are some illusions being spread about Singapore transitioning to a genuine bourgeois democracy as the legitimacy of the PAP wanes. The PAP is more than happy to indulge these illusions, with the full understanding that the Singaporean state cannot exist outside of PAP control, so complete is the fusing of the party and the state. The outgoing prime minister Lee Hsien Loong admitted as much at a recent party conference.

This highlights the hypocrisy of many in the Western media, who hold up Lee as a “visionary pragmatist,” a model of statesmanship to be emulated by the West as capitalist regimes across the globe are in a crisis of legitimacy. From the perspective of the parasitic bourgeois, he was indeed a “visionary pragmatist” who succeeded in defending their privileges and property rights against the growing revolutionary tide of the 1950s. However, the hopes of today’s bourgeoisie in repeating Lee’s success are misplaced. Our period is one of crisis, revolutions and counter-revolutions and one in which the working class has been immensely strengthened.

Today, while Singaporean citizens still enjoy a standard of living significantly higher than their brothers and sisters of the region, this has only come about by Singapore becoming an imperialist power unto itself in addition to being a hub for US and Chinese finance capital. Singapore is the biggest source of Foreign Direct Investment for Indonesia, Myanmar, Vietnam, Thailand, and is the second largest for Malaysia. Singaporean capital’s huge influence in the region is facilitated by the state project “Enterprise Singapore,” which oversees over 2,000 projects around Southeast Asia for Singaporean capital to invest in.

These investments - rather than contributing to the local economies - are parasitic in nature, exploiting the cheap labour of workers in the region as well as causing catastrophic environmental damage through large palm oil plantations and land reclamation projects. This is not to mention the hundreds of thousands of Bangladeshi and Indian migrant workers who labour in slave-like conditions to keep Singapore clean and vibrant.

The workers of Singapore and the region must have no illusions about the smiling mask of bourgeois democracy, which barely covers the bloody face of imperialism. Genuine democratic rights can only be won in the battle of the working class for a socialist revolution that will free the workers and the oppressed of the entire region. The PAP regime has long maintained that it defended Singapore from the menace of communism. In this coming period, however, genuine communism is poised to make a world-historic reappearance and the PAP will have none of the advantages of the past with which it defended the inequality and barbarity of the capitalist system.

If you are a revolutionary communist who wants to see the end of the capitalist system the world over, join us!